Apache Kafka is deceptively easy to adopt and hard to govern at scale. In many large organizations, Kafka starts as a simple messaging backbone and slowly turns into a critical dependency for dozens of applications and teams. Over time, clusters multiply, versions drift apart, and your existing processes cannot keep up.

This post is about what happened when we walked into that kind of setup. As a small platform team, we had to bring order to 78 Kafka clusters across 17 environments, with 10,000+ topics and nearly 40,000 partitions, running everything from Kafka 0.8.2 to 4.x. This was not a new greenfield platform. It was a messy real system where production stability was non negotiable.

If you are an SRE or platform engineer inheriting multiple Kafka clusters and dealing with tickets, drift, and audits, this story is for you.

When Kafka outgrows "TicketOps"

When we arrived at the client, Kafka was already part of the critical path for many services. No one had stopped to ask what happens when you run it at this scale with informal processes.

Here is what we saw.

1. Two people owned every change

There were only two Kafka administrators for the entire organization. They owned all topic changes, ACL updates, and most production checks.

If a team wanted a new topic or a small config change, they had to raise a ticket. The average turnaround for a simple request was 3 to 5 days. For teams shipping frequently, this delay broke release plans and encouraged unsafe workarounds.

2. ClickOps everywhere and silent drift

Most topics were created via Kafka UIs such as CMAK or KafkaUI. There were no strong naming rules. Replication factors and retention settings varied by environment.

3. Security entropy by default

ACLs were easy to grant and hard to clean up. Over time, permissions piled up. No one could quickly answer basic questions like “who can read this topic” or “why does this service still have access”.

Removing access felt dangerous because the impact was unclear. So people avoided it, which made things worse.

At this point, Kafka was not the problem. The way they operated Kafka was.

Embracing legacy software

Our first thought was simple. Pick a modern Kafka management tool. Use its APIs to put everything under control.

Then we hit a recurring UnsupportedVersionException when we tried to talk to some clusters. We used kafka-broker-api-version.sh to inspect them more closely.

That is when we realized some production clusters were still on Kafka 0.8.2.

This was not some minor upgrade gap. It was released back in Feb 2015, the current version as of writing the post is Kafka 4.1.1.

Kafka 0.8.2 does not support ACL APIs. There is no way to list or manage permissions using the same patterns that work on modern clusters.

That single fact broke many of the “standard” ideas we had in mind:

we could not force everything through a shiny modern operator.

we could not demand “upgrade first” before we fixed governance.

we could not rely on tools that assumed features that did not exist in 0.8.2.

The system had to work with the Kafka that was already in production.

Evaluating solutions

We then looked at common industry approaches and asked a simple question. Would this survive our real constraints?

Kubernetes operators

Strimzi and similar operators are great if most of your Kafka runs inside Kubernetes and on newer versions. Our clusters did not fit that pattern. Some were not on Kubernetes. Some were on very old versions.

We did not want our entire governance model to depend on an operator that could not talk to our oldest production clusters.

Terraform providers

Terraform is strong for infrastructure as code. The Kafka providers we tried introduced their own problems around state files, drift, and version mismatches. There was also no official, long term supported provider we were comfortable betting on.

For a lean platform team, this felt like extra weight.

Upgrade everything first

In theory, upgrading every cluster to Kafka 4.x would simplify life. In practice, it meant touching hundreds of dependent applications and accepting a lot of regression risk.

We could not pause the business for a large upgrade wave just to make our tooling easier.

We also needed portability

We knew that some clusters might move to managed services later, such as AWS MSK, Confluent, or Aiven. Any approach that locked us tightly into one runtime or control plane was a bad fit.

So we wanted Kafka GitOps without heavy control planes or strict Kubernetes dependency.

All of this pointed us at a different kind of solution. A lightweight, version aware governance layer that spoke Kafka directly. That led us to Jikkou.

Jikkou is an open‑source “Resource as Code” framework for Apache Kafka that lets you declaratively manage, automate, and provision Kafka resources like topics, ACLs, quotas, schemas, and connectors using YAML files. It is used as a CLI or REST service in GitOps-style workflows so platform teams and developers can self‑serve Kafka changes safely and reproducibly.

Establishing GIT as the only only source of truth

Once we understood the constraints, we made one clear rule.

If a Kafka topic or ACL was not in git, it did not exist.

Instead of treating UIs and shell commands as the source of truth, we flipped it. Git became the place where you declare what should exist. The system’s job was to reconcile that desired state with each cluster.

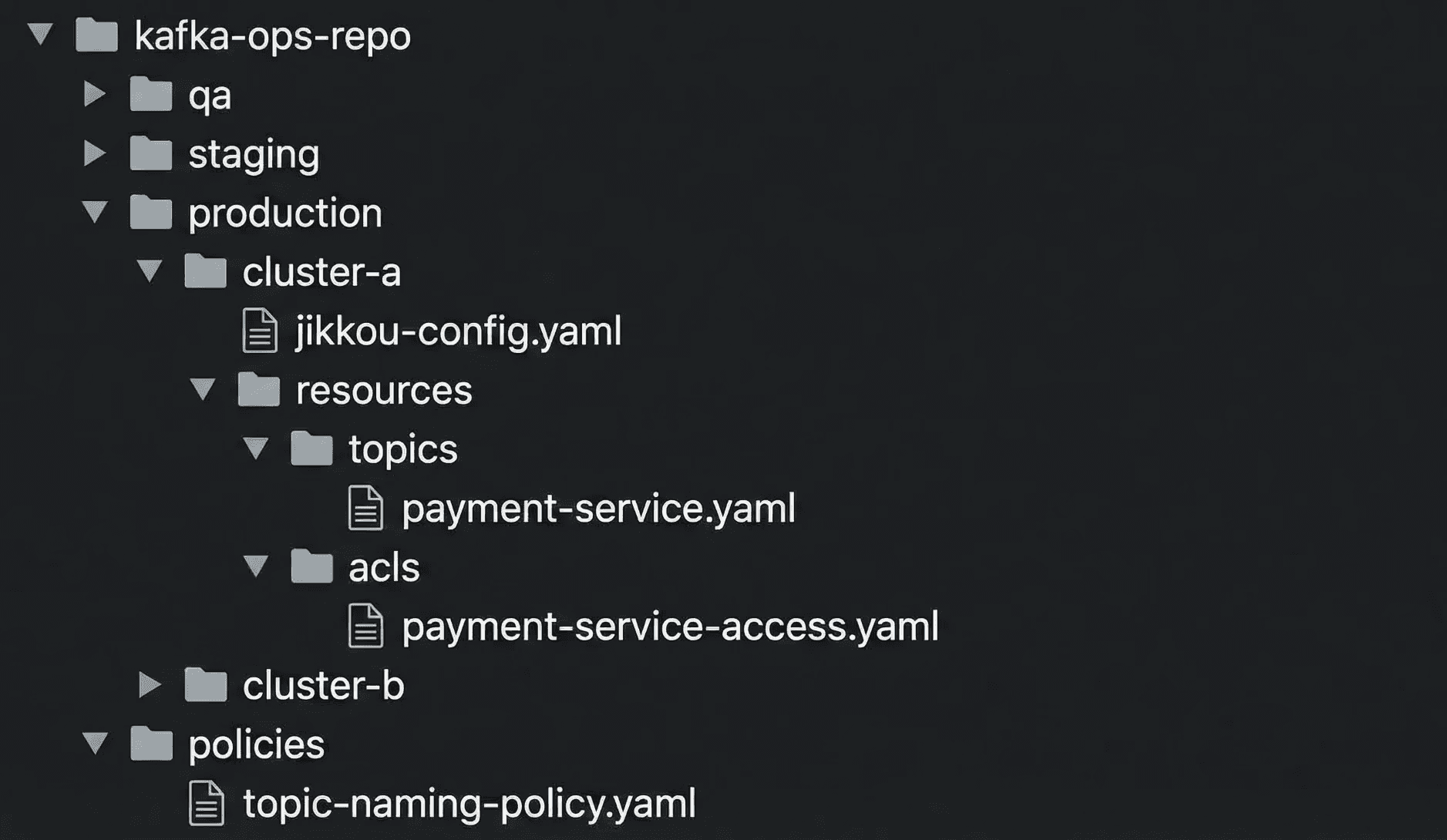

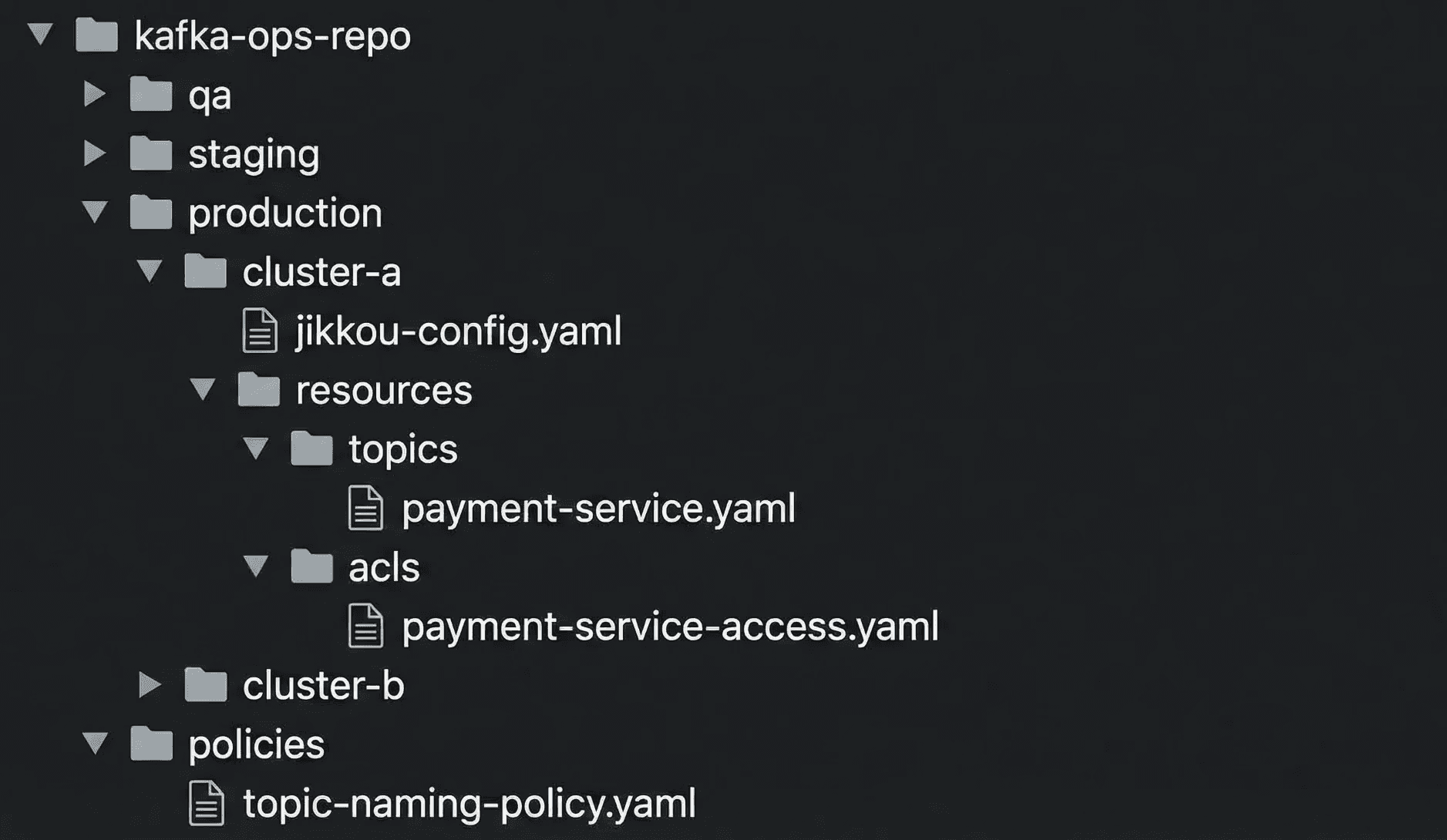

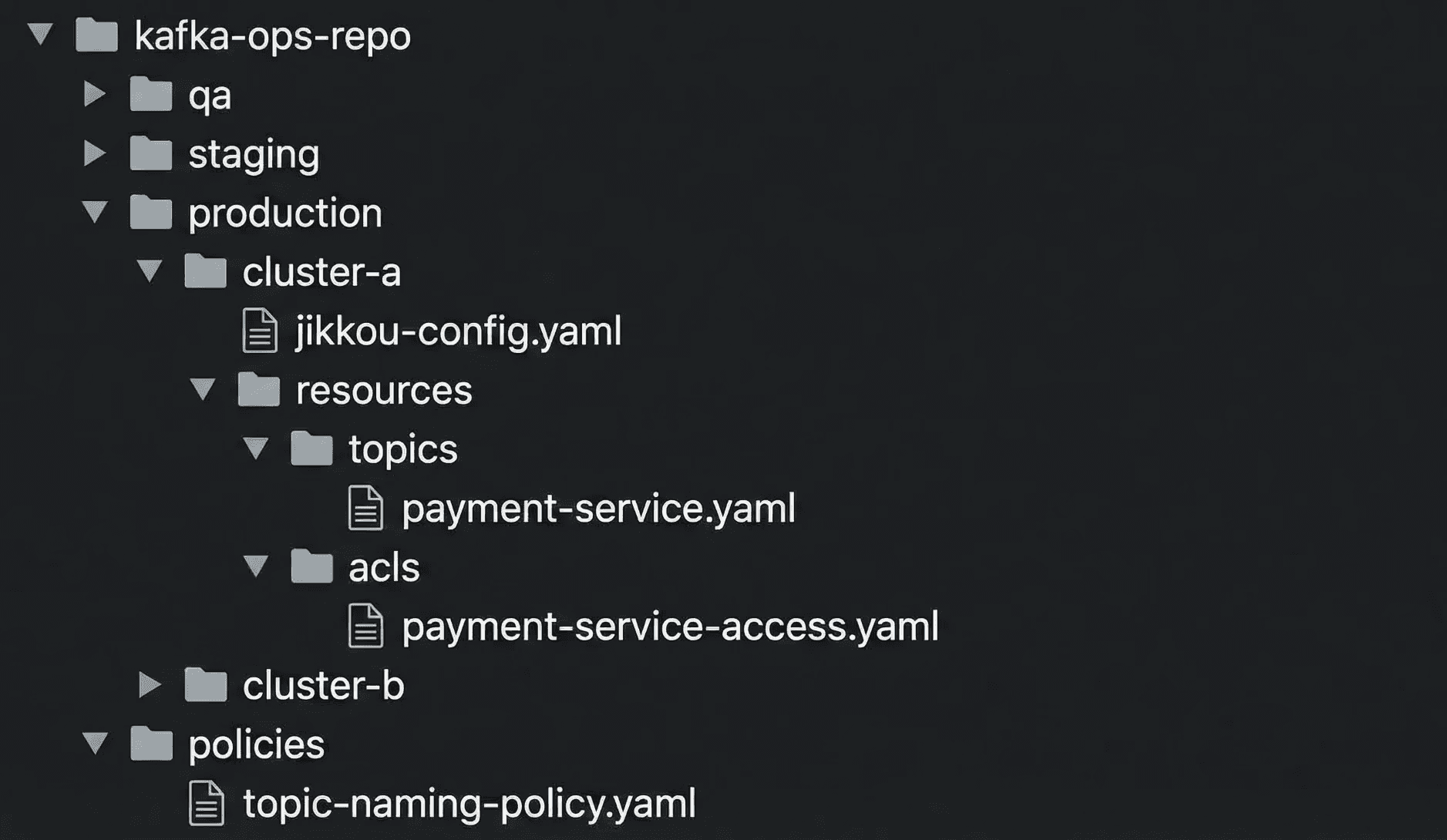

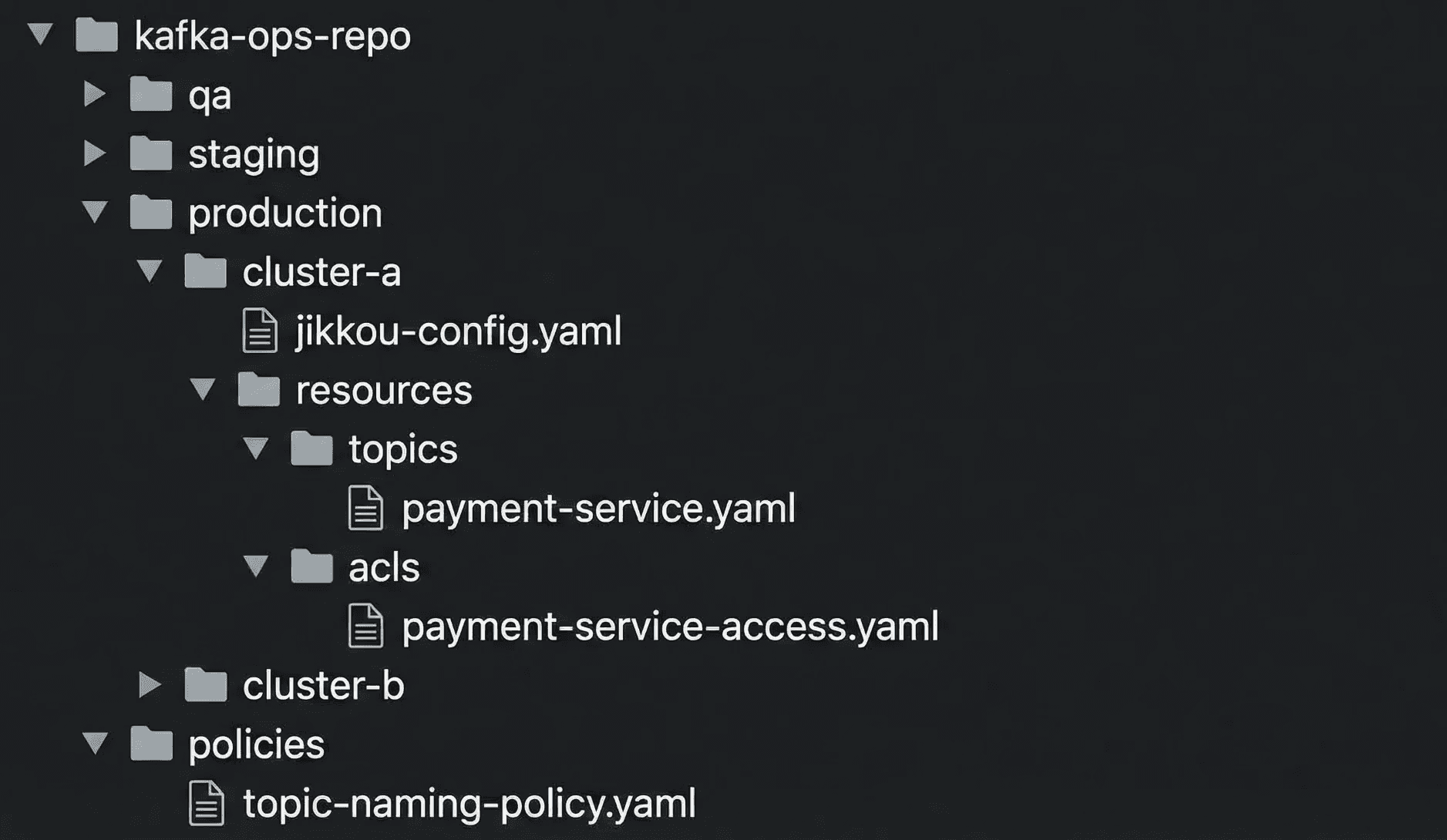

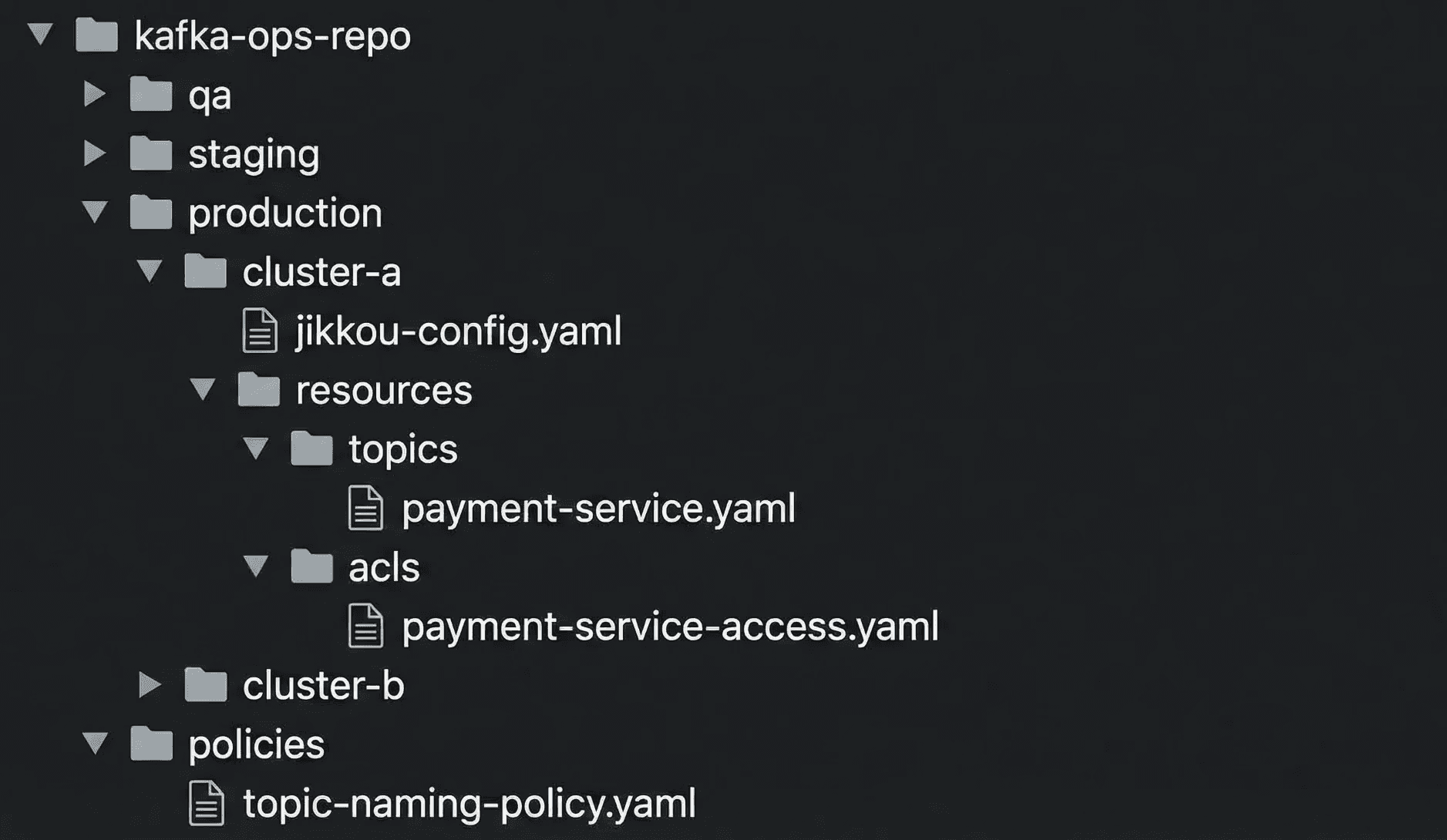

How we shaped the repo

We aligned the repository with how the organization worked.

separate directories for each environment such as qa, staging, and production.

cluster metadata files that describe bootstrap servers and Kafka version.

a CODEOWNERS file that makes ownership explicit.

Fig 1: Repo structure

Platform engineers own cluster level metadata. Application teams own their topics and ACLs. This change removed the two person bottleneck but kept clear control boundaries.

Step 1: Making Kafka declarative using Jikkou

We replaced manual CLI usage with structured yaml resources.

A topic file captures name, partitions, replicas, and config in one place. For example:

# topics/payment-service/transactions.yaml apiVersion: "kafka.jikkou.io/v1beta2" kind: "KafkaTopic" metadata: name: "payments-processed-v1" labels: cost-center: "finance" spec: partitions: 3 replicas: 3 config: min.insync.replicas: 2 cleanup.policy: "compact"

Eg: Sample Topic Configuration

This one file now encodes naming, cost, and durability decisions that used to live in someone’s head or in a wiki page.

We applied the same idea to ACLs. Each application gets a single file that defines its access profile instead of a scattered set of commands.

# consumers/payment-service-access.yaml apiVersion: "kafka.jikkou.io/v1" kind: "KafkaUser" metadata: name: "payment-service" spec: authentications: - type: "scram-sha-512" iterations: 4096 --- apiVersion: "kafka.jikkou.io/v1beta2" kind: "KafkaPrincipalAuthorization" metadata: name: "User:payment-service" spec: acls: - resource: type: "topic" pattern: "payments-processed-v1" patternType: "literal" operations: - "READ" - "DESCRIBE" host: "*"

Eg: Sample User and ACL Configuration

Now when someone asks “who can read this topic”, we search git, not terminals or screenshots.

Jikkou’s resource model hides differences between Kafka versions, so the same yaml patterns work across old and new clusters where possible.

Step 2: Making reconciliation safe and cheap

Declaring everything as code was the first step. The next step was to safely push that state to 78 clusters without causing incidents.

We focused on three ideas.

1. Only touch what changed

Running a full reconciliation across the entire fleet on every commit would be slow and noisy. So we added a “context selection” stage in the pipeline.

The pipeline uses git diff to see which environment folders changed in a merge request. It then configures Jikkou to target only the relevant clusters.

This keeps the blast radius small and keeps the pipeline fast.

2. Deletions must be explicit

Jikkou can detect when something exists in a cluster but not in git and treat it as a candidate for deletion. That is powerful and dangerous.

To prevent accidental "fat-finger" wipes, Jikkou enforces that removing a topic requires an explicit signal. The yaml must carry an annotation such as jikkou.io/delete: true before the system will delete it.

This forces the engineer to signal intent, ensuring that a cleanup script or a bad merge doesn't silently wipe production data.

3. Push rules into the pipeline, not slides

Instead of writing “best practices” in a document, we encoded them as validation rules in the pipeline.

Some examples:

cost controls: block topics that request extreme retention by validating

retention.ms.reliability: enforce minimum partition counts so new topics support basic parallelism.

legacy safety: for 0.8.2 clusters, block configs that are not supported to avoid silent failures.

This way, people learn the rules by writing configs and seeing clear errors, not by reading a long wiki page.

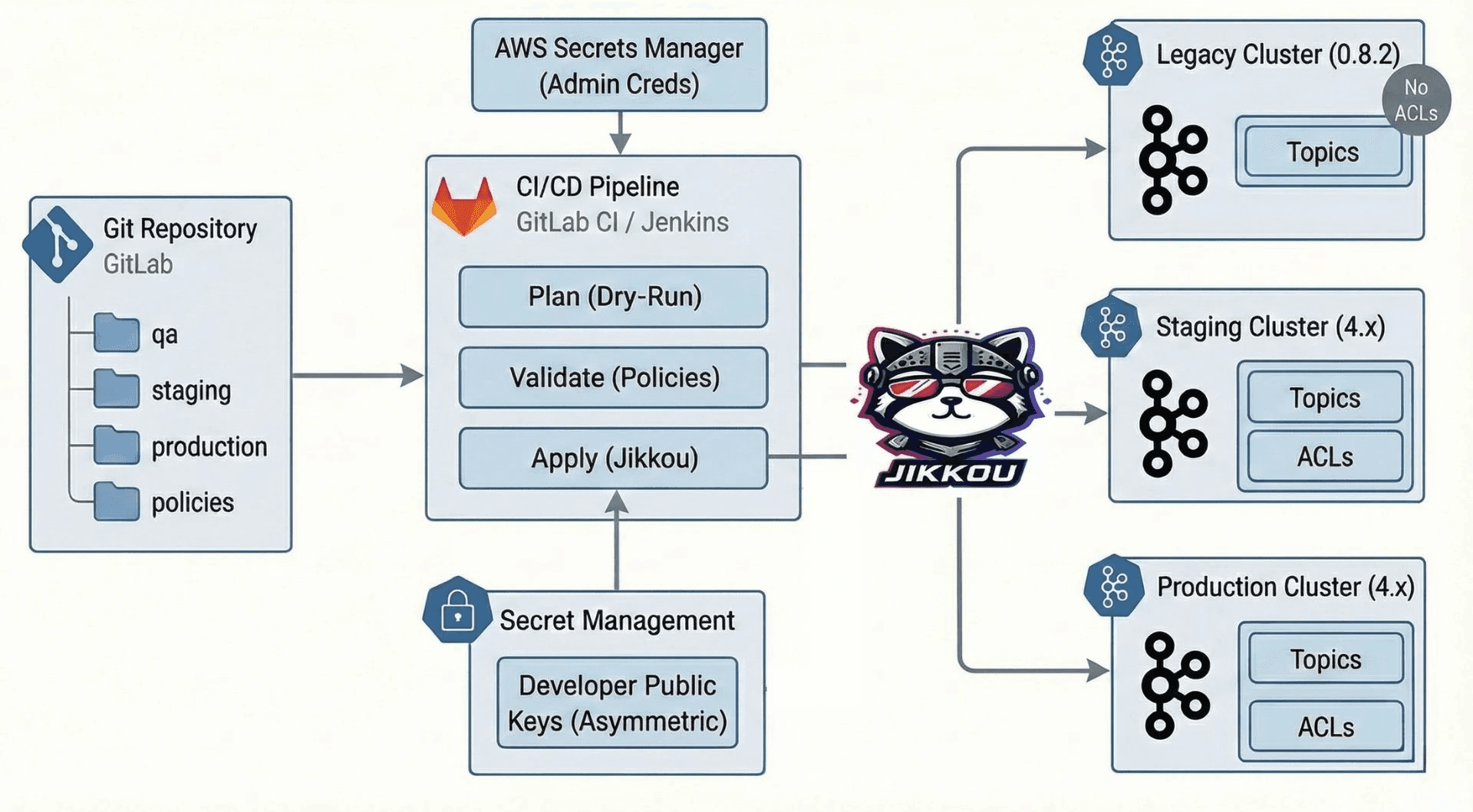

Step 3: Turning CLI access into a GitOps loop

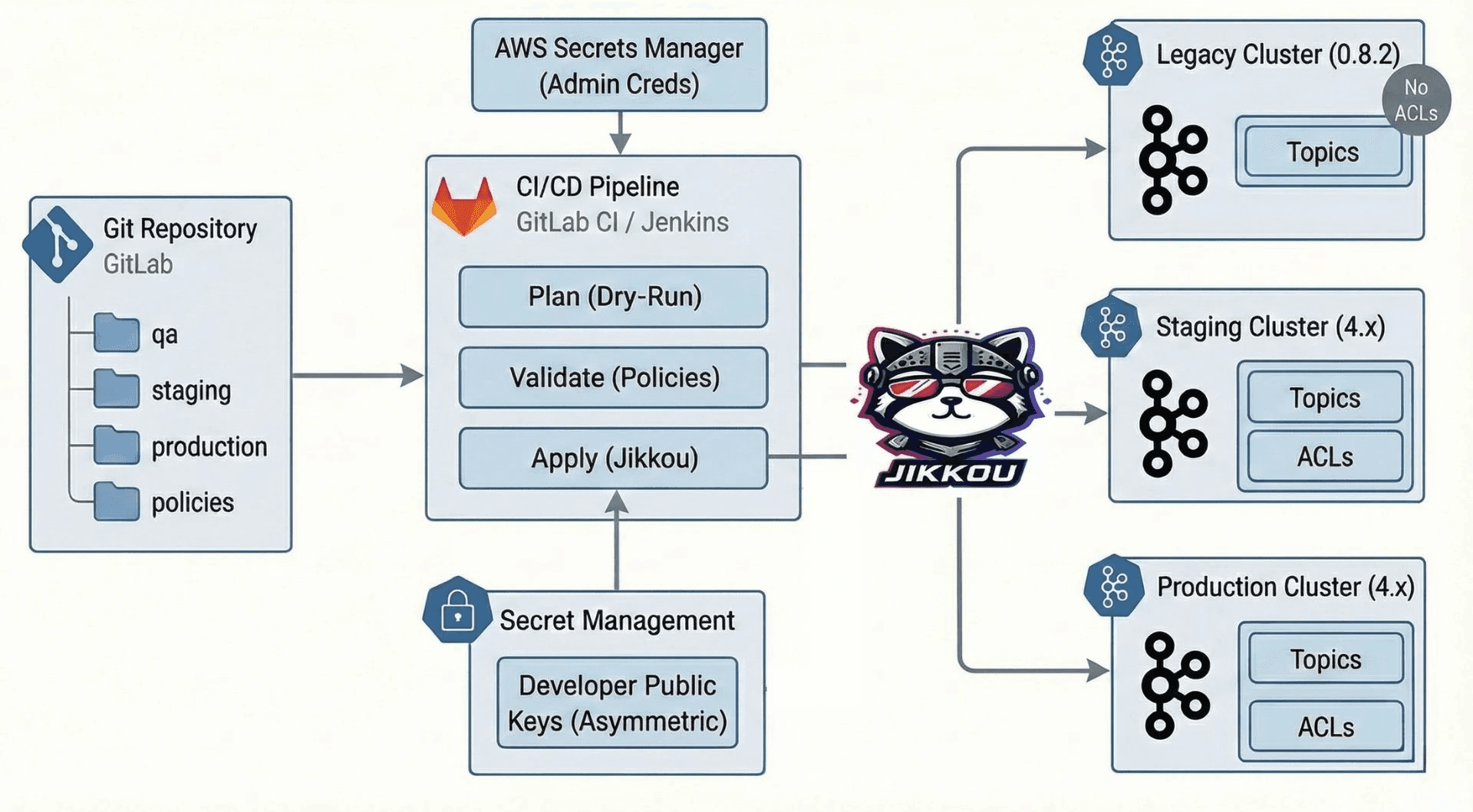

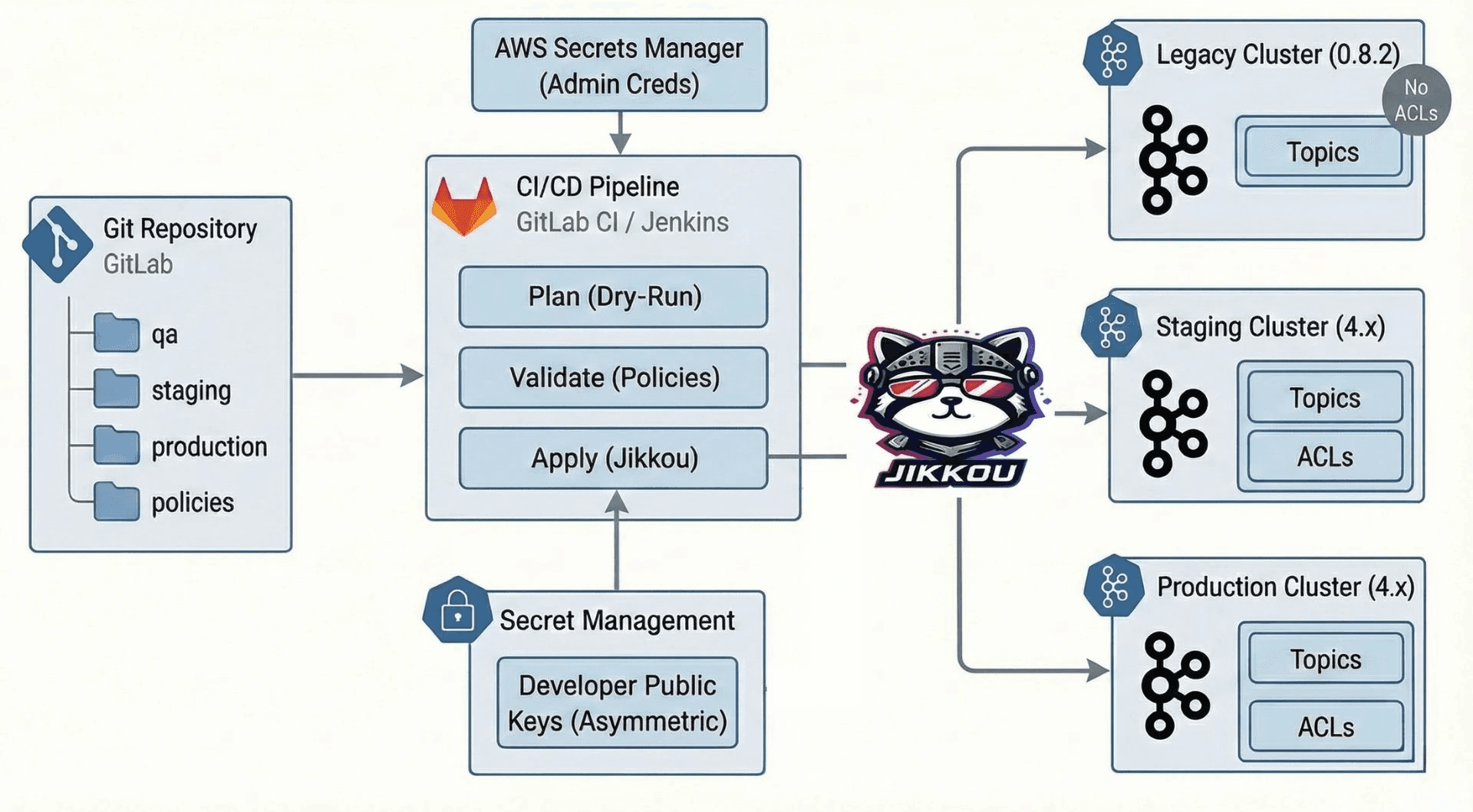

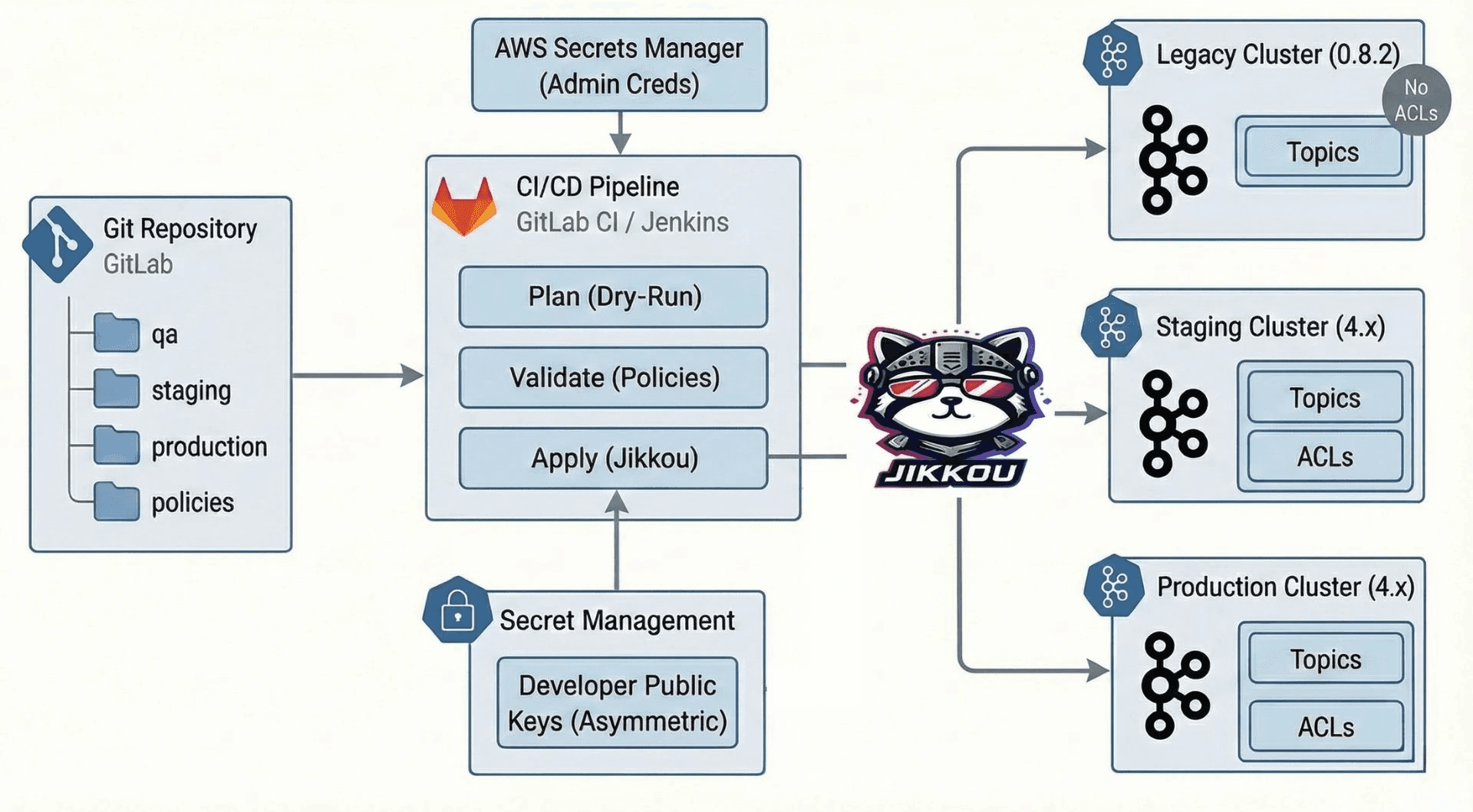

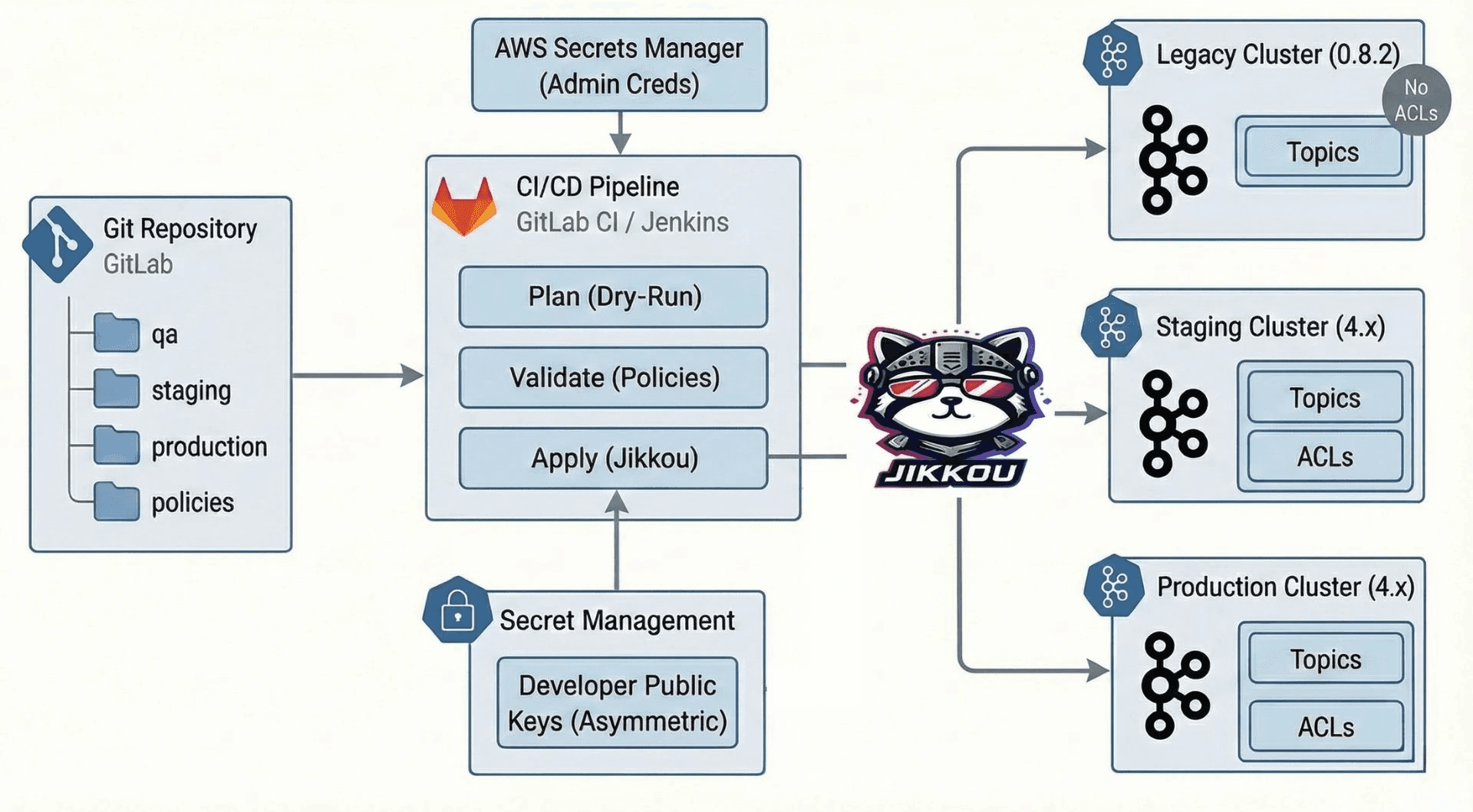

With the pieces above in place, we built a simple flow in our CI/CD system.

Fig 2: Workflow diagram

Plan a dry run

Every merge request triggers a dry run. The job shows exactly what will change on each cluster. New topics, config changes, and ACL updates are visible before anything is applied.

Validate the policies

The same run applies all the guards we talked about. If a change violates naming rules or tries to set an unsafe config, the pipeline fails.

Apply phase

Only changes that have passed review and are merged into the main branch are applied. Git history becomes the change log and rollback tool.

This took us from “give me shell on the Kafka box” to “open a pull request and wait for the pipeline”.

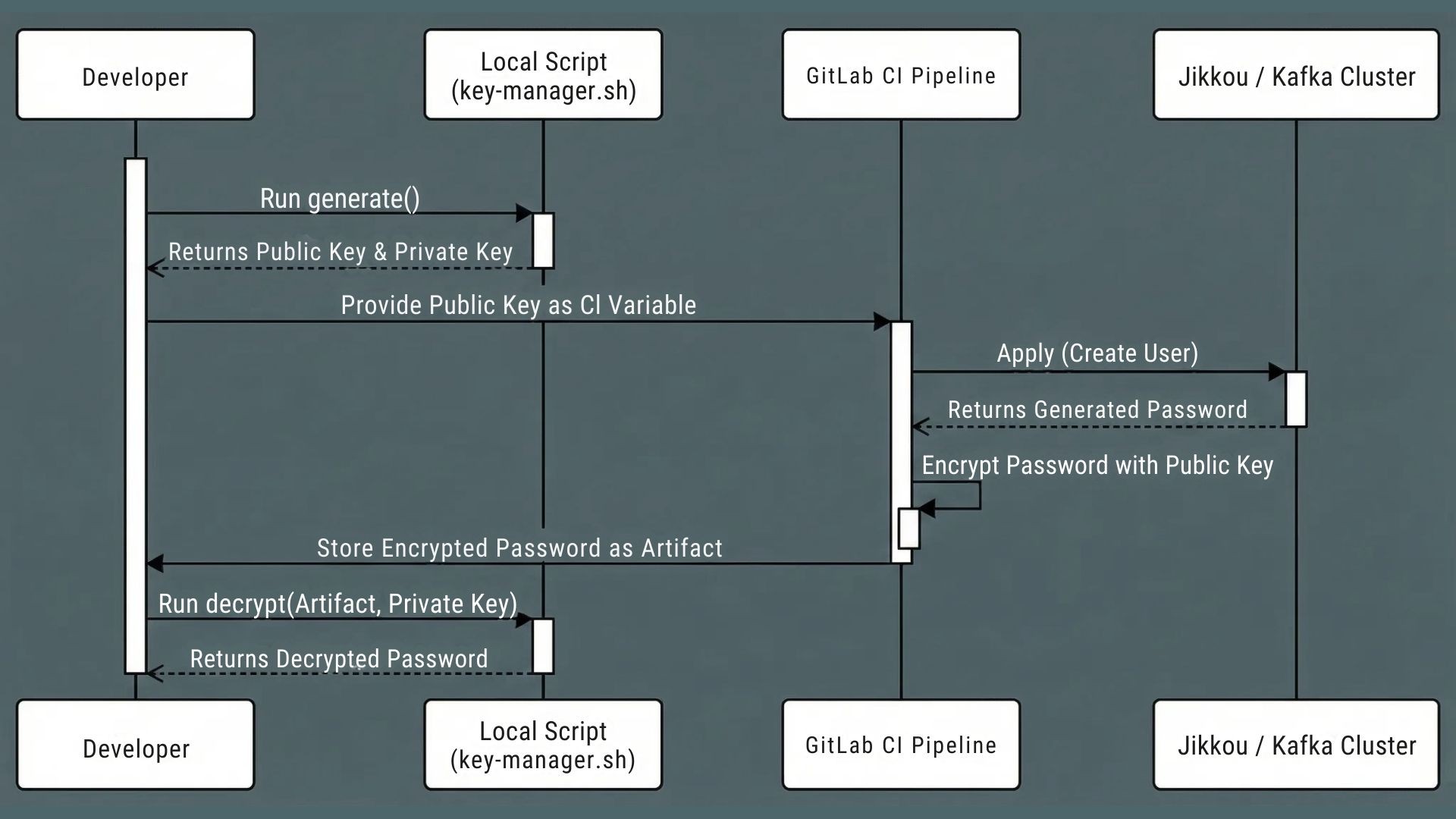

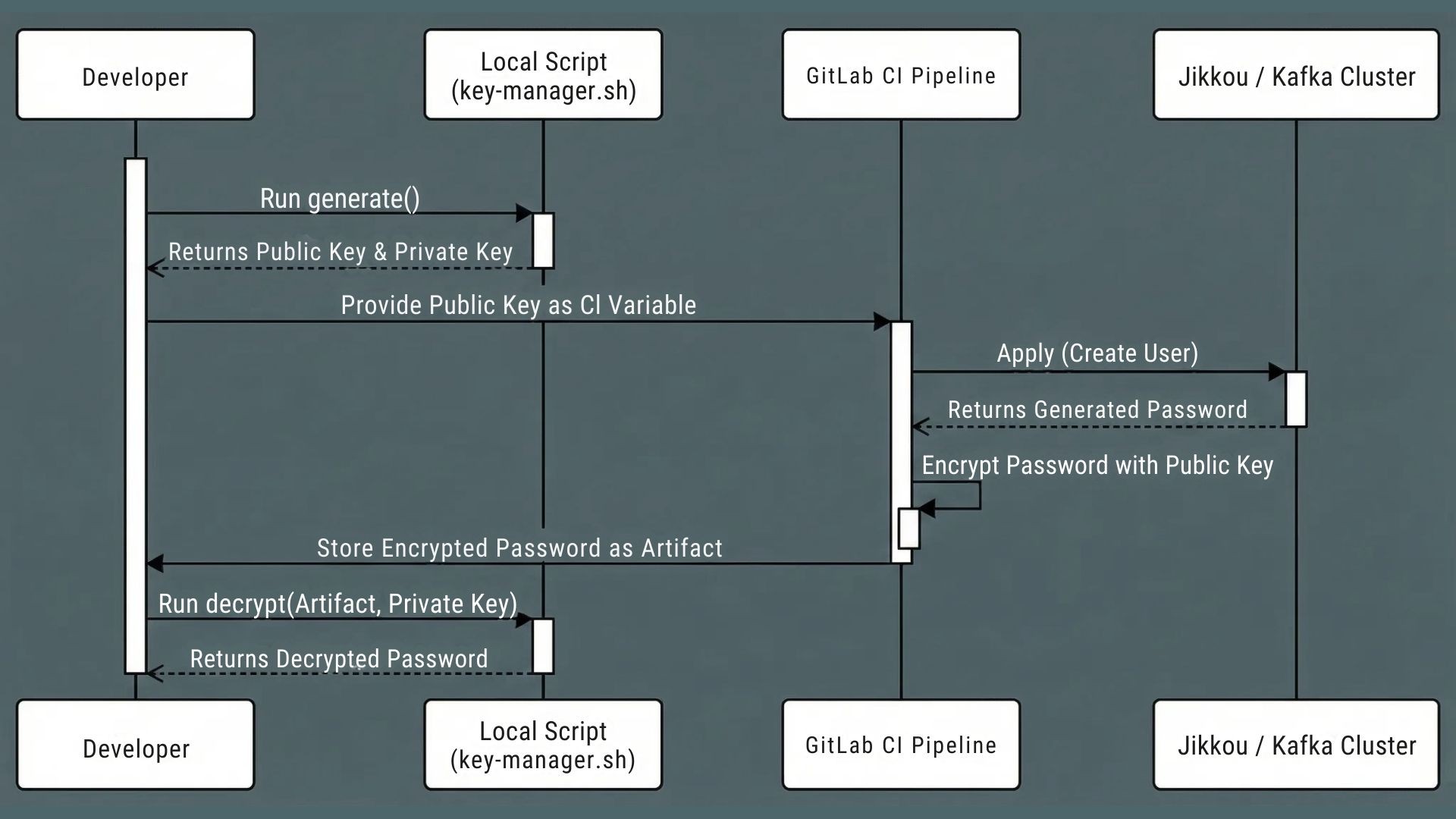

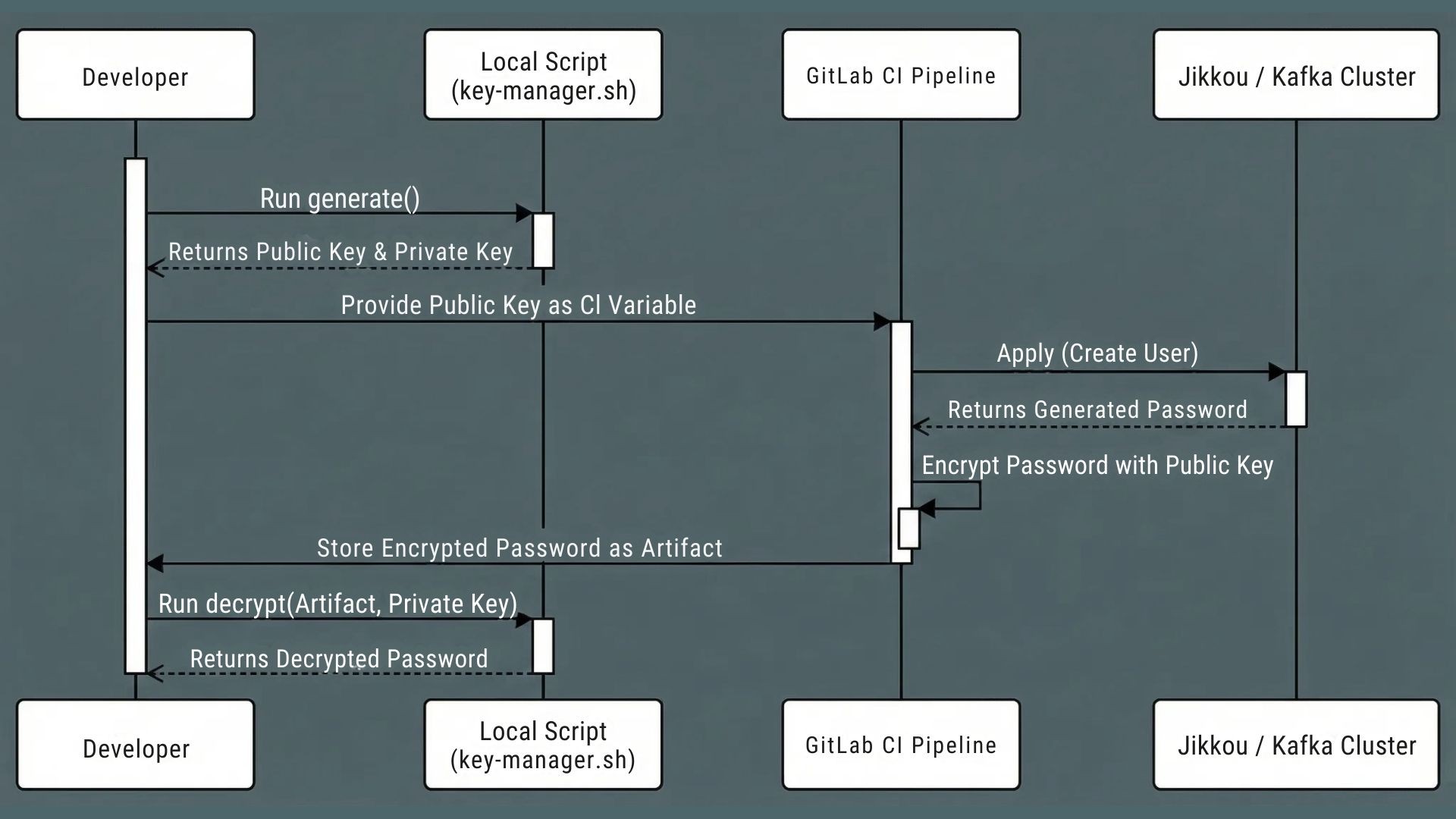

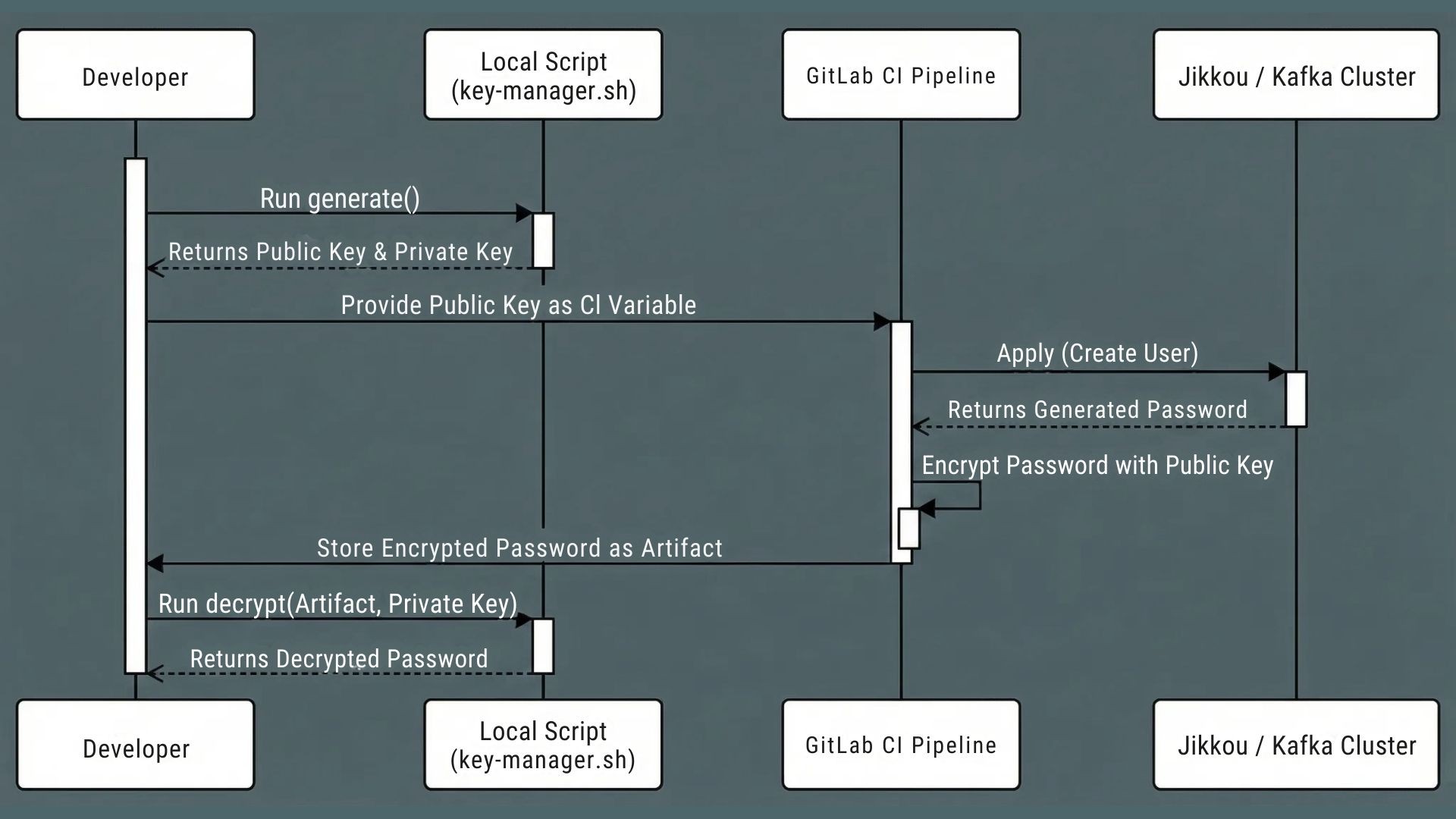

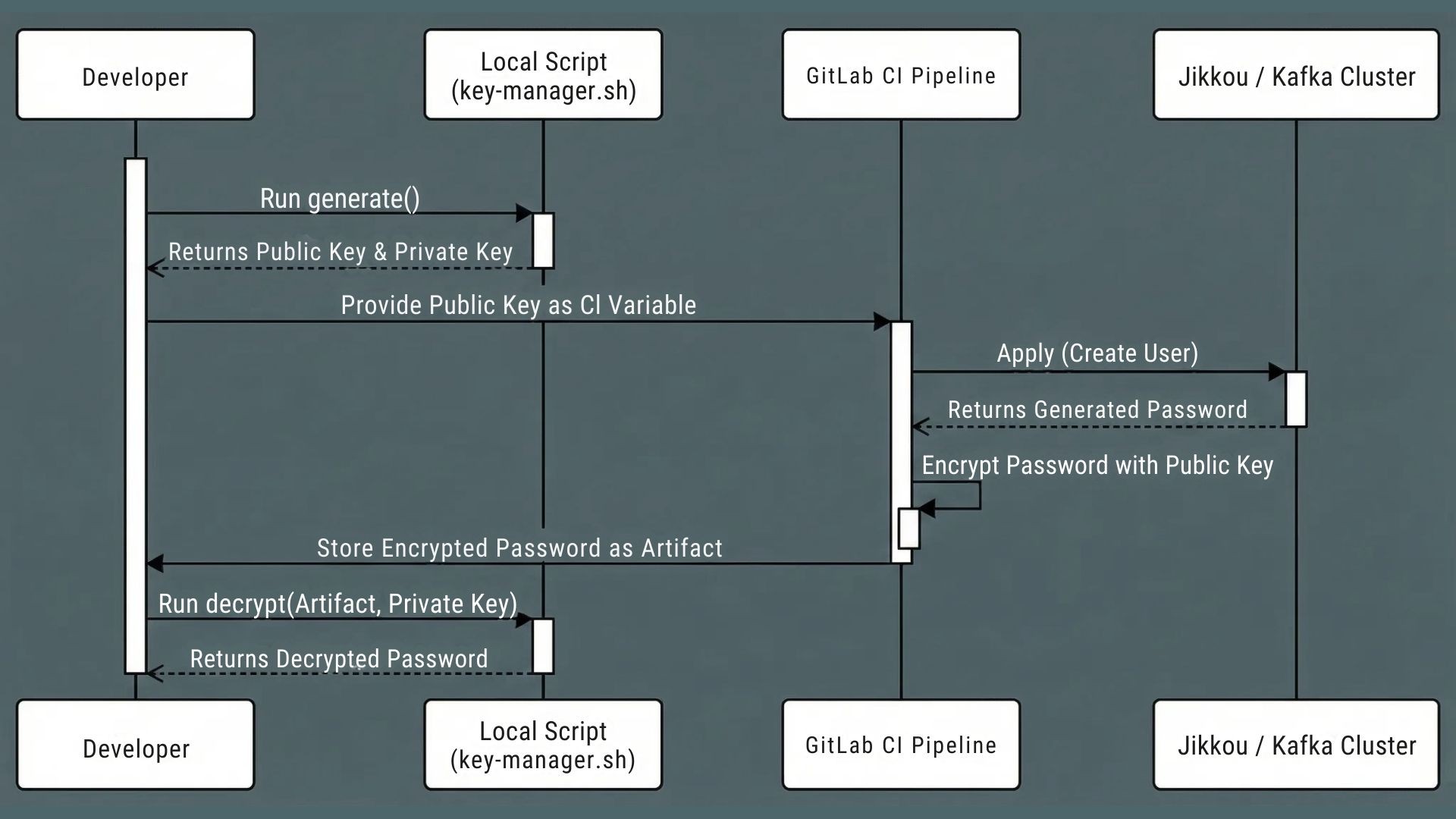

Step 4: A bonus "secret zero" problem we did not expect

Once topics and ACLs were under git control, another problem appeared.

Creating Kafka users for applications was easy with Jikkou. Creating passwords was easy too. Delivering those passwords securely to teams was not.

We first thought of reusing AWS Secrets Manager. That would have meant giving many application teams IAM access across 17 environments. The risk and operational overhead were too high.

So we built a different flow inside GitLab.

developers generate an RSA key pair locally using a helper script called

key-manager.sh.they pass the base64 public key as a ci variable when they run the pipeline.

the pipeline creates the Kafka user, captures the generated password, encrypts it with the public key, and stores it as an artifact.

the developer downloads the artifact and decrypts it using their private key, which never leaves their machine.

This way, we did not need a central secret store for application credentials, and only the owning team could read the password.

Fig 3: user credential generation workflow

What this changed in practice

After a few cycles of iteration, the impact was clear.

topic creation time went from days to minutes.

access reviews became a search in git instead of an investigation across tools.

platform engineers stopped acting as a hard gate and started designing better defaults and rules.

legacy clusters stayed stable while we gradually brought them under the same governance model.

Most importantly, Kafka moved from “fragile shared dependency” to “managed platform”.

Lessons for platform teams

Looking back, here are the lessons we would keep.

Governance is what actually needs to scale

Kafka scales by design. Your human process usually does not. GitOps lets a small platform team support many product teams without drowning in tickets.

Respect the systems you already have

You will not always get to upgrade everything before you improve it. Good tooling adapts to legacy clusters and modern ones at the same time.

Git is the real audit log

Dashboards are helpful, but when something goes wrong, you want to know who changed what and when. Git gives you that for free.

Prefer simple tools that fit your constraints

We avoided heavy control planes that did not match our environment. A small, focused tool that understands Kafka versions was a better fit.

Guardrails are better than human gatekeepers

The more you rely on a few people to approve every safe change, the slower you move. It is better to design clear rules, encode them in pipelines, and let teams move inside those boundaries.

Engineering for the world in hand

This story is not about the perfect GitOps stack. It is about making Kafka governable in the world you already run.

By treating topics and ACLs as code, using tools that respect old and new clusters, and putting rules into pipelines instead of docs, we turned an overloaded admin pair into a platform that many teams could use safely.

If you are staring at multiple Kafka clusters, unclear access, and a long ticket queue, you do not have to redesign everything at once. Start by making git the source of truth for one cluster, add guardrails, and grow from there.

If you are in a similar place

Designing a production ready Kafka governance model is not just about tools or operators. It needs the right git workflows, guardrails, and a plan that works even when you have old clusters in the mix.

At One2N, we help platform and SRE teams turn “kafka chaos” into a git driven platform that teams can trust. Whether you are stuck with legacy versions, drowning in tickets, or worried about breaking production, our consulting team can help you design and roll out a gitops for Kafka model that fits your reality.

Apache Kafka is deceptively easy to adopt and hard to govern at scale. In many large organizations, Kafka starts as a simple messaging backbone and slowly turns into a critical dependency for dozens of applications and teams. Over time, clusters multiply, versions drift apart, and your existing processes cannot keep up.

This post is about what happened when we walked into that kind of setup. As a small platform team, we had to bring order to 78 Kafka clusters across 17 environments, with 10,000+ topics and nearly 40,000 partitions, running everything from Kafka 0.8.2 to 4.x. This was not a new greenfield platform. It was a messy real system where production stability was non negotiable.

If you are an SRE or platform engineer inheriting multiple Kafka clusters and dealing with tickets, drift, and audits, this story is for you.

When Kafka outgrows "TicketOps"

When we arrived at the client, Kafka was already part of the critical path for many services. No one had stopped to ask what happens when you run it at this scale with informal processes.

Here is what we saw.

1. Two people owned every change

There were only two Kafka administrators for the entire organization. They owned all topic changes, ACL updates, and most production checks.

If a team wanted a new topic or a small config change, they had to raise a ticket. The average turnaround for a simple request was 3 to 5 days. For teams shipping frequently, this delay broke release plans and encouraged unsafe workarounds.

2. ClickOps everywhere and silent drift

Most topics were created via Kafka UIs such as CMAK or KafkaUI. There were no strong naming rules. Replication factors and retention settings varied by environment.

3. Security entropy by default

ACLs were easy to grant and hard to clean up. Over time, permissions piled up. No one could quickly answer basic questions like “who can read this topic” or “why does this service still have access”.

Removing access felt dangerous because the impact was unclear. So people avoided it, which made things worse.

At this point, Kafka was not the problem. The way they operated Kafka was.

Embracing legacy software

Our first thought was simple. Pick a modern Kafka management tool. Use its APIs to put everything under control.

Then we hit a recurring UnsupportedVersionException when we tried to talk to some clusters. We used kafka-broker-api-version.sh to inspect them more closely.

That is when we realized some production clusters were still on Kafka 0.8.2.

This was not some minor upgrade gap. It was released back in Feb 2015, the current version as of writing the post is Kafka 4.1.1.

Kafka 0.8.2 does not support ACL APIs. There is no way to list or manage permissions using the same patterns that work on modern clusters.

That single fact broke many of the “standard” ideas we had in mind:

we could not force everything through a shiny modern operator.

we could not demand “upgrade first” before we fixed governance.

we could not rely on tools that assumed features that did not exist in 0.8.2.

The system had to work with the Kafka that was already in production.

Evaluating solutions

We then looked at common industry approaches and asked a simple question. Would this survive our real constraints?

Kubernetes operators

Strimzi and similar operators are great if most of your Kafka runs inside Kubernetes and on newer versions. Our clusters did not fit that pattern. Some were not on Kubernetes. Some were on very old versions.

We did not want our entire governance model to depend on an operator that could not talk to our oldest production clusters.

Terraform providers

Terraform is strong for infrastructure as code. The Kafka providers we tried introduced their own problems around state files, drift, and version mismatches. There was also no official, long term supported provider we were comfortable betting on.

For a lean platform team, this felt like extra weight.

Upgrade everything first

In theory, upgrading every cluster to Kafka 4.x would simplify life. In practice, it meant touching hundreds of dependent applications and accepting a lot of regression risk.

We could not pause the business for a large upgrade wave just to make our tooling easier.

We also needed portability

We knew that some clusters might move to managed services later, such as AWS MSK, Confluent, or Aiven. Any approach that locked us tightly into one runtime or control plane was a bad fit.

So we wanted Kafka GitOps without heavy control planes or strict Kubernetes dependency.

All of this pointed us at a different kind of solution. A lightweight, version aware governance layer that spoke Kafka directly. That led us to Jikkou.

Jikkou is an open‑source “Resource as Code” framework for Apache Kafka that lets you declaratively manage, automate, and provision Kafka resources like topics, ACLs, quotas, schemas, and connectors using YAML files. It is used as a CLI or REST service in GitOps-style workflows so platform teams and developers can self‑serve Kafka changes safely and reproducibly.

Establishing GIT as the only only source of truth

Once we understood the constraints, we made one clear rule.

If a Kafka topic or ACL was not in git, it did not exist.

Instead of treating UIs and shell commands as the source of truth, we flipped it. Git became the place where you declare what should exist. The system’s job was to reconcile that desired state with each cluster.

How we shaped the repo

We aligned the repository with how the organization worked.

separate directories for each environment such as qa, staging, and production.

cluster metadata files that describe bootstrap servers and Kafka version.

a CODEOWNERS file that makes ownership explicit.

Fig 1: Repo structure

Platform engineers own cluster level metadata. Application teams own their topics and ACLs. This change removed the two person bottleneck but kept clear control boundaries.

Step 1: Making Kafka declarative using Jikkou

We replaced manual CLI usage with structured yaml resources.

A topic file captures name, partitions, replicas, and config in one place. For example:

# topics/payment-service/transactions.yaml apiVersion: "kafka.jikkou.io/v1beta2" kind: "KafkaTopic" metadata: name: "payments-processed-v1" labels: cost-center: "finance" spec: partitions: 3 replicas: 3 config: min.insync.replicas: 2 cleanup.policy: "compact"

Eg: Sample Topic Configuration

This one file now encodes naming, cost, and durability decisions that used to live in someone’s head or in a wiki page.

We applied the same idea to ACLs. Each application gets a single file that defines its access profile instead of a scattered set of commands.

# consumers/payment-service-access.yaml apiVersion: "kafka.jikkou.io/v1" kind: "KafkaUser" metadata: name: "payment-service" spec: authentications: - type: "scram-sha-512" iterations: 4096 --- apiVersion: "kafka.jikkou.io/v1beta2" kind: "KafkaPrincipalAuthorization" metadata: name: "User:payment-service" spec: acls: - resource: type: "topic" pattern: "payments-processed-v1" patternType: "literal" operations: - "READ" - "DESCRIBE" host: "*"

Eg: Sample User and ACL Configuration

Now when someone asks “who can read this topic”, we search git, not terminals or screenshots.

Jikkou’s resource model hides differences between Kafka versions, so the same yaml patterns work across old and new clusters where possible.

Step 2: Making reconciliation safe and cheap

Declaring everything as code was the first step. The next step was to safely push that state to 78 clusters without causing incidents.

We focused on three ideas.

1. Only touch what changed

Running a full reconciliation across the entire fleet on every commit would be slow and noisy. So we added a “context selection” stage in the pipeline.

The pipeline uses git diff to see which environment folders changed in a merge request. It then configures Jikkou to target only the relevant clusters.

This keeps the blast radius small and keeps the pipeline fast.

2. Deletions must be explicit

Jikkou can detect when something exists in a cluster but not in git and treat it as a candidate for deletion. That is powerful and dangerous.

To prevent accidental "fat-finger" wipes, Jikkou enforces that removing a topic requires an explicit signal. The yaml must carry an annotation such as jikkou.io/delete: true before the system will delete it.

This forces the engineer to signal intent, ensuring that a cleanup script or a bad merge doesn't silently wipe production data.

3. Push rules into the pipeline, not slides

Instead of writing “best practices” in a document, we encoded them as validation rules in the pipeline.

Some examples:

cost controls: block topics that request extreme retention by validating

retention.ms.reliability: enforce minimum partition counts so new topics support basic parallelism.

legacy safety: for 0.8.2 clusters, block configs that are not supported to avoid silent failures.

This way, people learn the rules by writing configs and seeing clear errors, not by reading a long wiki page.

Step 3: Turning CLI access into a GitOps loop

With the pieces above in place, we built a simple flow in our CI/CD system.

Fig 2: Workflow diagram

Plan a dry run

Every merge request triggers a dry run. The job shows exactly what will change on each cluster. New topics, config changes, and ACL updates are visible before anything is applied.

Validate the policies

The same run applies all the guards we talked about. If a change violates naming rules or tries to set an unsafe config, the pipeline fails.

Apply phase

Only changes that have passed review and are merged into the main branch are applied. Git history becomes the change log and rollback tool.

This took us from “give me shell on the Kafka box” to “open a pull request and wait for the pipeline”.

Step 4: A bonus "secret zero" problem we did not expect

Once topics and ACLs were under git control, another problem appeared.

Creating Kafka users for applications was easy with Jikkou. Creating passwords was easy too. Delivering those passwords securely to teams was not.

We first thought of reusing AWS Secrets Manager. That would have meant giving many application teams IAM access across 17 environments. The risk and operational overhead were too high.

So we built a different flow inside GitLab.

developers generate an RSA key pair locally using a helper script called

key-manager.sh.they pass the base64 public key as a ci variable when they run the pipeline.

the pipeline creates the Kafka user, captures the generated password, encrypts it with the public key, and stores it as an artifact.

the developer downloads the artifact and decrypts it using their private key, which never leaves their machine.

This way, we did not need a central secret store for application credentials, and only the owning team could read the password.

Fig 3: user credential generation workflow

What this changed in practice

After a few cycles of iteration, the impact was clear.

topic creation time went from days to minutes.

access reviews became a search in git instead of an investigation across tools.

platform engineers stopped acting as a hard gate and started designing better defaults and rules.

legacy clusters stayed stable while we gradually brought them under the same governance model.

Most importantly, Kafka moved from “fragile shared dependency” to “managed platform”.

Lessons for platform teams

Looking back, here are the lessons we would keep.

Governance is what actually needs to scale

Kafka scales by design. Your human process usually does not. GitOps lets a small platform team support many product teams without drowning in tickets.

Respect the systems you already have

You will not always get to upgrade everything before you improve it. Good tooling adapts to legacy clusters and modern ones at the same time.

Git is the real audit log

Dashboards are helpful, but when something goes wrong, you want to know who changed what and when. Git gives you that for free.

Prefer simple tools that fit your constraints

We avoided heavy control planes that did not match our environment. A small, focused tool that understands Kafka versions was a better fit.

Guardrails are better than human gatekeepers

The more you rely on a few people to approve every safe change, the slower you move. It is better to design clear rules, encode them in pipelines, and let teams move inside those boundaries.

Engineering for the world in hand

This story is not about the perfect GitOps stack. It is about making Kafka governable in the world you already run.

By treating topics and ACLs as code, using tools that respect old and new clusters, and putting rules into pipelines instead of docs, we turned an overloaded admin pair into a platform that many teams could use safely.

If you are staring at multiple Kafka clusters, unclear access, and a long ticket queue, you do not have to redesign everything at once. Start by making git the source of truth for one cluster, add guardrails, and grow from there.

If you are in a similar place

Designing a production ready Kafka governance model is not just about tools or operators. It needs the right git workflows, guardrails, and a plan that works even when you have old clusters in the mix.

At One2N, we help platform and SRE teams turn “kafka chaos” into a git driven platform that teams can trust. Whether you are stuck with legacy versions, drowning in tickets, or worried about breaking production, our consulting team can help you design and roll out a gitops for Kafka model that fits your reality.

Apache Kafka is deceptively easy to adopt and hard to govern at scale. In many large organizations, Kafka starts as a simple messaging backbone and slowly turns into a critical dependency for dozens of applications and teams. Over time, clusters multiply, versions drift apart, and your existing processes cannot keep up.

This post is about what happened when we walked into that kind of setup. As a small platform team, we had to bring order to 78 Kafka clusters across 17 environments, with 10,000+ topics and nearly 40,000 partitions, running everything from Kafka 0.8.2 to 4.x. This was not a new greenfield platform. It was a messy real system where production stability was non negotiable.

If you are an SRE or platform engineer inheriting multiple Kafka clusters and dealing with tickets, drift, and audits, this story is for you.

When Kafka outgrows "TicketOps"

When we arrived at the client, Kafka was already part of the critical path for many services. No one had stopped to ask what happens when you run it at this scale with informal processes.

Here is what we saw.

1. Two people owned every change

There were only two Kafka administrators for the entire organization. They owned all topic changes, ACL updates, and most production checks.

If a team wanted a new topic or a small config change, they had to raise a ticket. The average turnaround for a simple request was 3 to 5 days. For teams shipping frequently, this delay broke release plans and encouraged unsafe workarounds.

2. ClickOps everywhere and silent drift

Most topics were created via Kafka UIs such as CMAK or KafkaUI. There were no strong naming rules. Replication factors and retention settings varied by environment.

3. Security entropy by default

ACLs were easy to grant and hard to clean up. Over time, permissions piled up. No one could quickly answer basic questions like “who can read this topic” or “why does this service still have access”.

Removing access felt dangerous because the impact was unclear. So people avoided it, which made things worse.

At this point, Kafka was not the problem. The way they operated Kafka was.

Embracing legacy software

Our first thought was simple. Pick a modern Kafka management tool. Use its APIs to put everything under control.

Then we hit a recurring UnsupportedVersionException when we tried to talk to some clusters. We used kafka-broker-api-version.sh to inspect them more closely.

That is when we realized some production clusters were still on Kafka 0.8.2.

This was not some minor upgrade gap. It was released back in Feb 2015, the current version as of writing the post is Kafka 4.1.1.

Kafka 0.8.2 does not support ACL APIs. There is no way to list or manage permissions using the same patterns that work on modern clusters.

That single fact broke many of the “standard” ideas we had in mind:

we could not force everything through a shiny modern operator.

we could not demand “upgrade first” before we fixed governance.

we could not rely on tools that assumed features that did not exist in 0.8.2.

The system had to work with the Kafka that was already in production.

Evaluating solutions

We then looked at common industry approaches and asked a simple question. Would this survive our real constraints?

Kubernetes operators

Strimzi and similar operators are great if most of your Kafka runs inside Kubernetes and on newer versions. Our clusters did not fit that pattern. Some were not on Kubernetes. Some were on very old versions.

We did not want our entire governance model to depend on an operator that could not talk to our oldest production clusters.

Terraform providers

Terraform is strong for infrastructure as code. The Kafka providers we tried introduced their own problems around state files, drift, and version mismatches. There was also no official, long term supported provider we were comfortable betting on.

For a lean platform team, this felt like extra weight.

Upgrade everything first

In theory, upgrading every cluster to Kafka 4.x would simplify life. In practice, it meant touching hundreds of dependent applications and accepting a lot of regression risk.

We could not pause the business for a large upgrade wave just to make our tooling easier.

We also needed portability

We knew that some clusters might move to managed services later, such as AWS MSK, Confluent, or Aiven. Any approach that locked us tightly into one runtime or control plane was a bad fit.

So we wanted Kafka GitOps without heavy control planes or strict Kubernetes dependency.

All of this pointed us at a different kind of solution. A lightweight, version aware governance layer that spoke Kafka directly. That led us to Jikkou.

Jikkou is an open‑source “Resource as Code” framework for Apache Kafka that lets you declaratively manage, automate, and provision Kafka resources like topics, ACLs, quotas, schemas, and connectors using YAML files. It is used as a CLI or REST service in GitOps-style workflows so platform teams and developers can self‑serve Kafka changes safely and reproducibly.

Establishing GIT as the only only source of truth

Once we understood the constraints, we made one clear rule.

If a Kafka topic or ACL was not in git, it did not exist.

Instead of treating UIs and shell commands as the source of truth, we flipped it. Git became the place where you declare what should exist. The system’s job was to reconcile that desired state with each cluster.

How we shaped the repo

We aligned the repository with how the organization worked.

separate directories for each environment such as qa, staging, and production.

cluster metadata files that describe bootstrap servers and Kafka version.

a CODEOWNERS file that makes ownership explicit.

Fig 1: Repo structure

Platform engineers own cluster level metadata. Application teams own their topics and ACLs. This change removed the two person bottleneck but kept clear control boundaries.

Step 1: Making Kafka declarative using Jikkou

We replaced manual CLI usage with structured yaml resources.

A topic file captures name, partitions, replicas, and config in one place. For example:

# topics/payment-service/transactions.yaml apiVersion: "kafka.jikkou.io/v1beta2" kind: "KafkaTopic" metadata: name: "payments-processed-v1" labels: cost-center: "finance" spec: partitions: 3 replicas: 3 config: min.insync.replicas: 2 cleanup.policy: "compact"

Eg: Sample Topic Configuration

This one file now encodes naming, cost, and durability decisions that used to live in someone’s head or in a wiki page.

We applied the same idea to ACLs. Each application gets a single file that defines its access profile instead of a scattered set of commands.

# consumers/payment-service-access.yaml apiVersion: "kafka.jikkou.io/v1" kind: "KafkaUser" metadata: name: "payment-service" spec: authentications: - type: "scram-sha-512" iterations: 4096 --- apiVersion: "kafka.jikkou.io/v1beta2" kind: "KafkaPrincipalAuthorization" metadata: name: "User:payment-service" spec: acls: - resource: type: "topic" pattern: "payments-processed-v1" patternType: "literal" operations: - "READ" - "DESCRIBE" host: "*"

Eg: Sample User and ACL Configuration

Now when someone asks “who can read this topic”, we search git, not terminals or screenshots.

Jikkou’s resource model hides differences between Kafka versions, so the same yaml patterns work across old and new clusters where possible.

Step 2: Making reconciliation safe and cheap

Declaring everything as code was the first step. The next step was to safely push that state to 78 clusters without causing incidents.

We focused on three ideas.

1. Only touch what changed

Running a full reconciliation across the entire fleet on every commit would be slow and noisy. So we added a “context selection” stage in the pipeline.

The pipeline uses git diff to see which environment folders changed in a merge request. It then configures Jikkou to target only the relevant clusters.

This keeps the blast radius small and keeps the pipeline fast.

2. Deletions must be explicit

Jikkou can detect when something exists in a cluster but not in git and treat it as a candidate for deletion. That is powerful and dangerous.

To prevent accidental "fat-finger" wipes, Jikkou enforces that removing a topic requires an explicit signal. The yaml must carry an annotation such as jikkou.io/delete: true before the system will delete it.

This forces the engineer to signal intent, ensuring that a cleanup script or a bad merge doesn't silently wipe production data.

3. Push rules into the pipeline, not slides

Instead of writing “best practices” in a document, we encoded them as validation rules in the pipeline.

Some examples:

cost controls: block topics that request extreme retention by validating

retention.ms.reliability: enforce minimum partition counts so new topics support basic parallelism.

legacy safety: for 0.8.2 clusters, block configs that are not supported to avoid silent failures.

This way, people learn the rules by writing configs and seeing clear errors, not by reading a long wiki page.

Step 3: Turning CLI access into a GitOps loop

With the pieces above in place, we built a simple flow in our CI/CD system.

Fig 2: Workflow diagram

Plan a dry run

Every merge request triggers a dry run. The job shows exactly what will change on each cluster. New topics, config changes, and ACL updates are visible before anything is applied.

Validate the policies

The same run applies all the guards we talked about. If a change violates naming rules or tries to set an unsafe config, the pipeline fails.

Apply phase

Only changes that have passed review and are merged into the main branch are applied. Git history becomes the change log and rollback tool.

This took us from “give me shell on the Kafka box” to “open a pull request and wait for the pipeline”.

Step 4: A bonus "secret zero" problem we did not expect

Once topics and ACLs were under git control, another problem appeared.

Creating Kafka users for applications was easy with Jikkou. Creating passwords was easy too. Delivering those passwords securely to teams was not.

We first thought of reusing AWS Secrets Manager. That would have meant giving many application teams IAM access across 17 environments. The risk and operational overhead were too high.

So we built a different flow inside GitLab.

developers generate an RSA key pair locally using a helper script called

key-manager.sh.they pass the base64 public key as a ci variable when they run the pipeline.

the pipeline creates the Kafka user, captures the generated password, encrypts it with the public key, and stores it as an artifact.

the developer downloads the artifact and decrypts it using their private key, which never leaves their machine.

This way, we did not need a central secret store for application credentials, and only the owning team could read the password.

Fig 3: user credential generation workflow

What this changed in practice

After a few cycles of iteration, the impact was clear.

topic creation time went from days to minutes.

access reviews became a search in git instead of an investigation across tools.

platform engineers stopped acting as a hard gate and started designing better defaults and rules.

legacy clusters stayed stable while we gradually brought them under the same governance model.

Most importantly, Kafka moved from “fragile shared dependency” to “managed platform”.

Lessons for platform teams

Looking back, here are the lessons we would keep.

Governance is what actually needs to scale

Kafka scales by design. Your human process usually does not. GitOps lets a small platform team support many product teams without drowning in tickets.

Respect the systems you already have

You will not always get to upgrade everything before you improve it. Good tooling adapts to legacy clusters and modern ones at the same time.

Git is the real audit log

Dashboards are helpful, but when something goes wrong, you want to know who changed what and when. Git gives you that for free.

Prefer simple tools that fit your constraints

We avoided heavy control planes that did not match our environment. A small, focused tool that understands Kafka versions was a better fit.

Guardrails are better than human gatekeepers

The more you rely on a few people to approve every safe change, the slower you move. It is better to design clear rules, encode them in pipelines, and let teams move inside those boundaries.

Engineering for the world in hand

This story is not about the perfect GitOps stack. It is about making Kafka governable in the world you already run.

By treating topics and ACLs as code, using tools that respect old and new clusters, and putting rules into pipelines instead of docs, we turned an overloaded admin pair into a platform that many teams could use safely.

If you are staring at multiple Kafka clusters, unclear access, and a long ticket queue, you do not have to redesign everything at once. Start by making git the source of truth for one cluster, add guardrails, and grow from there.

If you are in a similar place

Designing a production ready Kafka governance model is not just about tools or operators. It needs the right git workflows, guardrails, and a plan that works even when you have old clusters in the mix.

At One2N, we help platform and SRE teams turn “kafka chaos” into a git driven platform that teams can trust. Whether you are stuck with legacy versions, drowning in tickets, or worried about breaking production, our consulting team can help you design and roll out a gitops for Kafka model that fits your reality.

Apache Kafka is deceptively easy to adopt and hard to govern at scale. In many large organizations, Kafka starts as a simple messaging backbone and slowly turns into a critical dependency for dozens of applications and teams. Over time, clusters multiply, versions drift apart, and your existing processes cannot keep up.

This post is about what happened when we walked into that kind of setup. As a small platform team, we had to bring order to 78 Kafka clusters across 17 environments, with 10,000+ topics and nearly 40,000 partitions, running everything from Kafka 0.8.2 to 4.x. This was not a new greenfield platform. It was a messy real system where production stability was non negotiable.

If you are an SRE or platform engineer inheriting multiple Kafka clusters and dealing with tickets, drift, and audits, this story is for you.

When Kafka outgrows "TicketOps"

When we arrived at the client, Kafka was already part of the critical path for many services. No one had stopped to ask what happens when you run it at this scale with informal processes.

Here is what we saw.

1. Two people owned every change

There were only two Kafka administrators for the entire organization. They owned all topic changes, ACL updates, and most production checks.

If a team wanted a new topic or a small config change, they had to raise a ticket. The average turnaround for a simple request was 3 to 5 days. For teams shipping frequently, this delay broke release plans and encouraged unsafe workarounds.

2. ClickOps everywhere and silent drift

Most topics were created via Kafka UIs such as CMAK or KafkaUI. There were no strong naming rules. Replication factors and retention settings varied by environment.

3. Security entropy by default

ACLs were easy to grant and hard to clean up. Over time, permissions piled up. No one could quickly answer basic questions like “who can read this topic” or “why does this service still have access”.

Removing access felt dangerous because the impact was unclear. So people avoided it, which made things worse.

At this point, Kafka was not the problem. The way they operated Kafka was.

Embracing legacy software

Our first thought was simple. Pick a modern Kafka management tool. Use its APIs to put everything under control.

Then we hit a recurring UnsupportedVersionException when we tried to talk to some clusters. We used kafka-broker-api-version.sh to inspect them more closely.

That is when we realized some production clusters were still on Kafka 0.8.2.

This was not some minor upgrade gap. It was released back in Feb 2015, the current version as of writing the post is Kafka 4.1.1.

Kafka 0.8.2 does not support ACL APIs. There is no way to list or manage permissions using the same patterns that work on modern clusters.

That single fact broke many of the “standard” ideas we had in mind:

we could not force everything through a shiny modern operator.

we could not demand “upgrade first” before we fixed governance.

we could not rely on tools that assumed features that did not exist in 0.8.2.

The system had to work with the Kafka that was already in production.

Evaluating solutions

We then looked at common industry approaches and asked a simple question. Would this survive our real constraints?

Kubernetes operators

Strimzi and similar operators are great if most of your Kafka runs inside Kubernetes and on newer versions. Our clusters did not fit that pattern. Some were not on Kubernetes. Some were on very old versions.

We did not want our entire governance model to depend on an operator that could not talk to our oldest production clusters.

Terraform providers

Terraform is strong for infrastructure as code. The Kafka providers we tried introduced their own problems around state files, drift, and version mismatches. There was also no official, long term supported provider we were comfortable betting on.

For a lean platform team, this felt like extra weight.

Upgrade everything first

In theory, upgrading every cluster to Kafka 4.x would simplify life. In practice, it meant touching hundreds of dependent applications and accepting a lot of regression risk.

We could not pause the business for a large upgrade wave just to make our tooling easier.

We also needed portability

We knew that some clusters might move to managed services later, such as AWS MSK, Confluent, or Aiven. Any approach that locked us tightly into one runtime or control plane was a bad fit.

So we wanted Kafka GitOps without heavy control planes or strict Kubernetes dependency.

All of this pointed us at a different kind of solution. A lightweight, version aware governance layer that spoke Kafka directly. That led us to Jikkou.

Jikkou is an open‑source “Resource as Code” framework for Apache Kafka that lets you declaratively manage, automate, and provision Kafka resources like topics, ACLs, quotas, schemas, and connectors using YAML files. It is used as a CLI or REST service in GitOps-style workflows so platform teams and developers can self‑serve Kafka changes safely and reproducibly.

Establishing GIT as the only only source of truth

Once we understood the constraints, we made one clear rule.

If a Kafka topic or ACL was not in git, it did not exist.

Instead of treating UIs and shell commands as the source of truth, we flipped it. Git became the place where you declare what should exist. The system’s job was to reconcile that desired state with each cluster.

How we shaped the repo

We aligned the repository with how the organization worked.

separate directories for each environment such as qa, staging, and production.

cluster metadata files that describe bootstrap servers and Kafka version.

a CODEOWNERS file that makes ownership explicit.

Fig 1: Repo structure

Platform engineers own cluster level metadata. Application teams own their topics and ACLs. This change removed the two person bottleneck but kept clear control boundaries.

Step 1: Making Kafka declarative using Jikkou

We replaced manual CLI usage with structured yaml resources.

A topic file captures name, partitions, replicas, and config in one place. For example:

# topics/payment-service/transactions.yaml apiVersion: "kafka.jikkou.io/v1beta2" kind: "KafkaTopic" metadata: name: "payments-processed-v1" labels: cost-center: "finance" spec: partitions: 3 replicas: 3 config: min.insync.replicas: 2 cleanup.policy: "compact"

Eg: Sample Topic Configuration

This one file now encodes naming, cost, and durability decisions that used to live in someone’s head or in a wiki page.

We applied the same idea to ACLs. Each application gets a single file that defines its access profile instead of a scattered set of commands.

# consumers/payment-service-access.yaml apiVersion: "kafka.jikkou.io/v1" kind: "KafkaUser" metadata: name: "payment-service" spec: authentications: - type: "scram-sha-512" iterations: 4096 --- apiVersion: "kafka.jikkou.io/v1beta2" kind: "KafkaPrincipalAuthorization" metadata: name: "User:payment-service" spec: acls: - resource: type: "topic" pattern: "payments-processed-v1" patternType: "literal" operations: - "READ" - "DESCRIBE" host: "*"

Eg: Sample User and ACL Configuration

Now when someone asks “who can read this topic”, we search git, not terminals or screenshots.

Jikkou’s resource model hides differences between Kafka versions, so the same yaml patterns work across old and new clusters where possible.

Step 2: Making reconciliation safe and cheap

Declaring everything as code was the first step. The next step was to safely push that state to 78 clusters without causing incidents.

We focused on three ideas.

1. Only touch what changed

Running a full reconciliation across the entire fleet on every commit would be slow and noisy. So we added a “context selection” stage in the pipeline.

The pipeline uses git diff to see which environment folders changed in a merge request. It then configures Jikkou to target only the relevant clusters.

This keeps the blast radius small and keeps the pipeline fast.

2. Deletions must be explicit

Jikkou can detect when something exists in a cluster but not in git and treat it as a candidate for deletion. That is powerful and dangerous.

To prevent accidental "fat-finger" wipes, Jikkou enforces that removing a topic requires an explicit signal. The yaml must carry an annotation such as jikkou.io/delete: true before the system will delete it.

This forces the engineer to signal intent, ensuring that a cleanup script or a bad merge doesn't silently wipe production data.

3. Push rules into the pipeline, not slides

Instead of writing “best practices” in a document, we encoded them as validation rules in the pipeline.

Some examples:

cost controls: block topics that request extreme retention by validating

retention.ms.reliability: enforce minimum partition counts so new topics support basic parallelism.

legacy safety: for 0.8.2 clusters, block configs that are not supported to avoid silent failures.

This way, people learn the rules by writing configs and seeing clear errors, not by reading a long wiki page.

Step 3: Turning CLI access into a GitOps loop

With the pieces above in place, we built a simple flow in our CI/CD system.

Fig 2: Workflow diagram

Plan a dry run

Every merge request triggers a dry run. The job shows exactly what will change on each cluster. New topics, config changes, and ACL updates are visible before anything is applied.

Validate the policies

The same run applies all the guards we talked about. If a change violates naming rules or tries to set an unsafe config, the pipeline fails.

Apply phase

Only changes that have passed review and are merged into the main branch are applied. Git history becomes the change log and rollback tool.

This took us from “give me shell on the Kafka box” to “open a pull request and wait for the pipeline”.

Step 4: A bonus "secret zero" problem we did not expect

Once topics and ACLs were under git control, another problem appeared.

Creating Kafka users for applications was easy with Jikkou. Creating passwords was easy too. Delivering those passwords securely to teams was not.

We first thought of reusing AWS Secrets Manager. That would have meant giving many application teams IAM access across 17 environments. The risk and operational overhead were too high.

So we built a different flow inside GitLab.

developers generate an RSA key pair locally using a helper script called

key-manager.sh.they pass the base64 public key as a ci variable when they run the pipeline.

the pipeline creates the Kafka user, captures the generated password, encrypts it with the public key, and stores it as an artifact.

the developer downloads the artifact and decrypts it using their private key, which never leaves their machine.

This way, we did not need a central secret store for application credentials, and only the owning team could read the password.

Fig 3: user credential generation workflow

What this changed in practice

After a few cycles of iteration, the impact was clear.

topic creation time went from days to minutes.

access reviews became a search in git instead of an investigation across tools.

platform engineers stopped acting as a hard gate and started designing better defaults and rules.

legacy clusters stayed stable while we gradually brought them under the same governance model.

Most importantly, Kafka moved from “fragile shared dependency” to “managed platform”.

Lessons for platform teams

Looking back, here are the lessons we would keep.

Governance is what actually needs to scale

Kafka scales by design. Your human process usually does not. GitOps lets a small platform team support many product teams without drowning in tickets.

Respect the systems you already have

You will not always get to upgrade everything before you improve it. Good tooling adapts to legacy clusters and modern ones at the same time.

Git is the real audit log

Dashboards are helpful, but when something goes wrong, you want to know who changed what and when. Git gives you that for free.

Prefer simple tools that fit your constraints

We avoided heavy control planes that did not match our environment. A small, focused tool that understands Kafka versions was a better fit.

Guardrails are better than human gatekeepers

The more you rely on a few people to approve every safe change, the slower you move. It is better to design clear rules, encode them in pipelines, and let teams move inside those boundaries.

Engineering for the world in hand

This story is not about the perfect GitOps stack. It is about making Kafka governable in the world you already run.

By treating topics and ACLs as code, using tools that respect old and new clusters, and putting rules into pipelines instead of docs, we turned an overloaded admin pair into a platform that many teams could use safely.

If you are staring at multiple Kafka clusters, unclear access, and a long ticket queue, you do not have to redesign everything at once. Start by making git the source of truth for one cluster, add guardrails, and grow from there.

If you are in a similar place

Designing a production ready Kafka governance model is not just about tools or operators. It needs the right git workflows, guardrails, and a plan that works even when you have old clusters in the mix.

At One2N, we help platform and SRE teams turn “kafka chaos” into a git driven platform that teams can trust. Whether you are stuck with legacy versions, drowning in tickets, or worried about breaking production, our consulting team can help you design and roll out a gitops for Kafka model that fits your reality.

Apache Kafka is deceptively easy to adopt and hard to govern at scale. In many large organizations, Kafka starts as a simple messaging backbone and slowly turns into a critical dependency for dozens of applications and teams. Over time, clusters multiply, versions drift apart, and your existing processes cannot keep up.

This post is about what happened when we walked into that kind of setup. As a small platform team, we had to bring order to 78 Kafka clusters across 17 environments, with 10,000+ topics and nearly 40,000 partitions, running everything from Kafka 0.8.2 to 4.x. This was not a new greenfield platform. It was a messy real system where production stability was non negotiable.

If you are an SRE or platform engineer inheriting multiple Kafka clusters and dealing with tickets, drift, and audits, this story is for you.

When Kafka outgrows "TicketOps"

When we arrived at the client, Kafka was already part of the critical path for many services. No one had stopped to ask what happens when you run it at this scale with informal processes.

Here is what we saw.

1. Two people owned every change

There were only two Kafka administrators for the entire organization. They owned all topic changes, ACL updates, and most production checks.

If a team wanted a new topic or a small config change, they had to raise a ticket. The average turnaround for a simple request was 3 to 5 days. For teams shipping frequently, this delay broke release plans and encouraged unsafe workarounds.

2. ClickOps everywhere and silent drift

Most topics were created via Kafka UIs such as CMAK or KafkaUI. There were no strong naming rules. Replication factors and retention settings varied by environment.

3. Security entropy by default

ACLs were easy to grant and hard to clean up. Over time, permissions piled up. No one could quickly answer basic questions like “who can read this topic” or “why does this service still have access”.

Removing access felt dangerous because the impact was unclear. So people avoided it, which made things worse.

At this point, Kafka was not the problem. The way they operated Kafka was.

Embracing legacy software

Our first thought was simple. Pick a modern Kafka management tool. Use its APIs to put everything under control.

Then we hit a recurring UnsupportedVersionException when we tried to talk to some clusters. We used kafka-broker-api-version.sh to inspect them more closely.

That is when we realized some production clusters were still on Kafka 0.8.2.

This was not some minor upgrade gap. It was released back in Feb 2015, the current version as of writing the post is Kafka 4.1.1.

Kafka 0.8.2 does not support ACL APIs. There is no way to list or manage permissions using the same patterns that work on modern clusters.

That single fact broke many of the “standard” ideas we had in mind:

we could not force everything through a shiny modern operator.

we could not demand “upgrade first” before we fixed governance.

we could not rely on tools that assumed features that did not exist in 0.8.2.

The system had to work with the Kafka that was already in production.

Evaluating solutions

We then looked at common industry approaches and asked a simple question. Would this survive our real constraints?

Kubernetes operators

Strimzi and similar operators are great if most of your Kafka runs inside Kubernetes and on newer versions. Our clusters did not fit that pattern. Some were not on Kubernetes. Some were on very old versions.

We did not want our entire governance model to depend on an operator that could not talk to our oldest production clusters.

Terraform providers

Terraform is strong for infrastructure as code. The Kafka providers we tried introduced their own problems around state files, drift, and version mismatches. There was also no official, long term supported provider we were comfortable betting on.

For a lean platform team, this felt like extra weight.

Upgrade everything first

In theory, upgrading every cluster to Kafka 4.x would simplify life. In practice, it meant touching hundreds of dependent applications and accepting a lot of regression risk.

We could not pause the business for a large upgrade wave just to make our tooling easier.

We also needed portability

We knew that some clusters might move to managed services later, such as AWS MSK, Confluent, or Aiven. Any approach that locked us tightly into one runtime or control plane was a bad fit.

So we wanted Kafka GitOps without heavy control planes or strict Kubernetes dependency.

All of this pointed us at a different kind of solution. A lightweight, version aware governance layer that spoke Kafka directly. That led us to Jikkou.

Jikkou is an open‑source “Resource as Code” framework for Apache Kafka that lets you declaratively manage, automate, and provision Kafka resources like topics, ACLs, quotas, schemas, and connectors using YAML files. It is used as a CLI or REST service in GitOps-style workflows so platform teams and developers can self‑serve Kafka changes safely and reproducibly.

Establishing GIT as the only only source of truth

Once we understood the constraints, we made one clear rule.

If a Kafka topic or ACL was not in git, it did not exist.

Instead of treating UIs and shell commands as the source of truth, we flipped it. Git became the place where you declare what should exist. The system’s job was to reconcile that desired state with each cluster.

How we shaped the repo

We aligned the repository with how the organization worked.

separate directories for each environment such as qa, staging, and production.

cluster metadata files that describe bootstrap servers and Kafka version.

a CODEOWNERS file that makes ownership explicit.

Fig 1: Repo structure

Platform engineers own cluster level metadata. Application teams own their topics and ACLs. This change removed the two person bottleneck but kept clear control boundaries.

Step 1: Making Kafka declarative using Jikkou

We replaced manual CLI usage with structured yaml resources.

A topic file captures name, partitions, replicas, and config in one place. For example:

# topics/payment-service/transactions.yaml apiVersion: "kafka.jikkou.io/v1beta2" kind: "KafkaTopic" metadata: name: "payments-processed-v1" labels: cost-center: "finance" spec: partitions: 3 replicas: 3 config: min.insync.replicas: 2 cleanup.policy: "compact"

Eg: Sample Topic Configuration

This one file now encodes naming, cost, and durability decisions that used to live in someone’s head or in a wiki page.

We applied the same idea to ACLs. Each application gets a single file that defines its access profile instead of a scattered set of commands.

# consumers/payment-service-access.yaml apiVersion: "kafka.jikkou.io/v1" kind: "KafkaUser" metadata: name: "payment-service" spec: authentications: - type: "scram-sha-512" iterations: 4096 --- apiVersion: "kafka.jikkou.io/v1beta2" kind: "KafkaPrincipalAuthorization" metadata: name: "User:payment-service" spec: acls: - resource: type: "topic" pattern: "payments-processed-v1" patternType: "literal" operations: - "READ" - "DESCRIBE" host: "*"

Eg: Sample User and ACL Configuration

Now when someone asks “who can read this topic”, we search git, not terminals or screenshots.

Jikkou’s resource model hides differences between Kafka versions, so the same yaml patterns work across old and new clusters where possible.

Step 2: Making reconciliation safe and cheap

Declaring everything as code was the first step. The next step was to safely push that state to 78 clusters without causing incidents.

We focused on three ideas.

1. Only touch what changed

Running a full reconciliation across the entire fleet on every commit would be slow and noisy. So we added a “context selection” stage in the pipeline.

The pipeline uses git diff to see which environment folders changed in a merge request. It then configures Jikkou to target only the relevant clusters.

This keeps the blast radius small and keeps the pipeline fast.

2. Deletions must be explicit

Jikkou can detect when something exists in a cluster but not in git and treat it as a candidate for deletion. That is powerful and dangerous.

To prevent accidental "fat-finger" wipes, Jikkou enforces that removing a topic requires an explicit signal. The yaml must carry an annotation such as jikkou.io/delete: true before the system will delete it.

This forces the engineer to signal intent, ensuring that a cleanup script or a bad merge doesn't silently wipe production data.

3. Push rules into the pipeline, not slides

Instead of writing “best practices” in a document, we encoded them as validation rules in the pipeline.

Some examples:

cost controls: block topics that request extreme retention by validating

retention.ms.reliability: enforce minimum partition counts so new topics support basic parallelism.

legacy safety: for 0.8.2 clusters, block configs that are not supported to avoid silent failures.

This way, people learn the rules by writing configs and seeing clear errors, not by reading a long wiki page.

Step 3: Turning CLI access into a GitOps loop

With the pieces above in place, we built a simple flow in our CI/CD system.

Fig 2: Workflow diagram

Plan a dry run

Every merge request triggers a dry run. The job shows exactly what will change on each cluster. New topics, config changes, and ACL updates are visible before anything is applied.

Validate the policies

The same run applies all the guards we talked about. If a change violates naming rules or tries to set an unsafe config, the pipeline fails.

Apply phase

Only changes that have passed review and are merged into the main branch are applied. Git history becomes the change log and rollback tool.

This took us from “give me shell on the Kafka box” to “open a pull request and wait for the pipeline”.

Step 4: A bonus "secret zero" problem we did not expect

Once topics and ACLs were under git control, another problem appeared.

Creating Kafka users for applications was easy with Jikkou. Creating passwords was easy too. Delivering those passwords securely to teams was not.

We first thought of reusing AWS Secrets Manager. That would have meant giving many application teams IAM access across 17 environments. The risk and operational overhead were too high.

So we built a different flow inside GitLab.

developers generate an RSA key pair locally using a helper script called

key-manager.sh.they pass the base64 public key as a ci variable when they run the pipeline.

the pipeline creates the Kafka user, captures the generated password, encrypts it with the public key, and stores it as an artifact.

the developer downloads the artifact and decrypts it using their private key, which never leaves their machine.

This way, we did not need a central secret store for application credentials, and only the owning team could read the password.

Fig 3: user credential generation workflow

What this changed in practice

After a few cycles of iteration, the impact was clear.

topic creation time went from days to minutes.

access reviews became a search in git instead of an investigation across tools.

platform engineers stopped acting as a hard gate and started designing better defaults and rules.

legacy clusters stayed stable while we gradually brought them under the same governance model.

Most importantly, Kafka moved from “fragile shared dependency” to “managed platform”.

Lessons for platform teams

Looking back, here are the lessons we would keep.

Governance is what actually needs to scale

Kafka scales by design. Your human process usually does not. GitOps lets a small platform team support many product teams without drowning in tickets.

Respect the systems you already have

You will not always get to upgrade everything before you improve it. Good tooling adapts to legacy clusters and modern ones at the same time.

Git is the real audit log

Dashboards are helpful, but when something goes wrong, you want to know who changed what and when. Git gives you that for free.

Prefer simple tools that fit your constraints

We avoided heavy control planes that did not match our environment. A small, focused tool that understands Kafka versions was a better fit.

Guardrails are better than human gatekeepers

The more you rely on a few people to approve every safe change, the slower you move. It is better to design clear rules, encode them in pipelines, and let teams move inside those boundaries.

Engineering for the world in hand

This story is not about the perfect GitOps stack. It is about making Kafka governable in the world you already run.

By treating topics and ACLs as code, using tools that respect old and new clusters, and putting rules into pipelines instead of docs, we turned an overloaded admin pair into a platform that many teams could use safely.

If you are staring at multiple Kafka clusters, unclear access, and a long ticket queue, you do not have to redesign everything at once. Start by making git the source of truth for one cluster, add guardrails, and grow from there.

If you are in a similar place

Designing a production ready Kafka governance model is not just about tools or operators. It needs the right git workflows, guardrails, and a plan that works even when you have old clusters in the mix.

At One2N, we help platform and SRE teams turn “kafka chaos” into a git driven platform that teams can trust. Whether you are stuck with legacy versions, drowning in tickets, or worried about breaking production, our consulting team can help you design and roll out a gitops for Kafka model that fits your reality.