I recently wrote about a concept that has stayed with me through every stage of my career: “Culture is not what you say, it is what you tolerate.”

It is easy to print values on a wall or run workshops on psychological safety. The hard part is that humans make mistakes. We are all prone to taking shortcuts when we are tired, under pressure, or overconfident. In high-stakes engineering, whether you are a funded startup or a $10B enterprise, those shortcuts are where the “lities” of a system begin to erode.

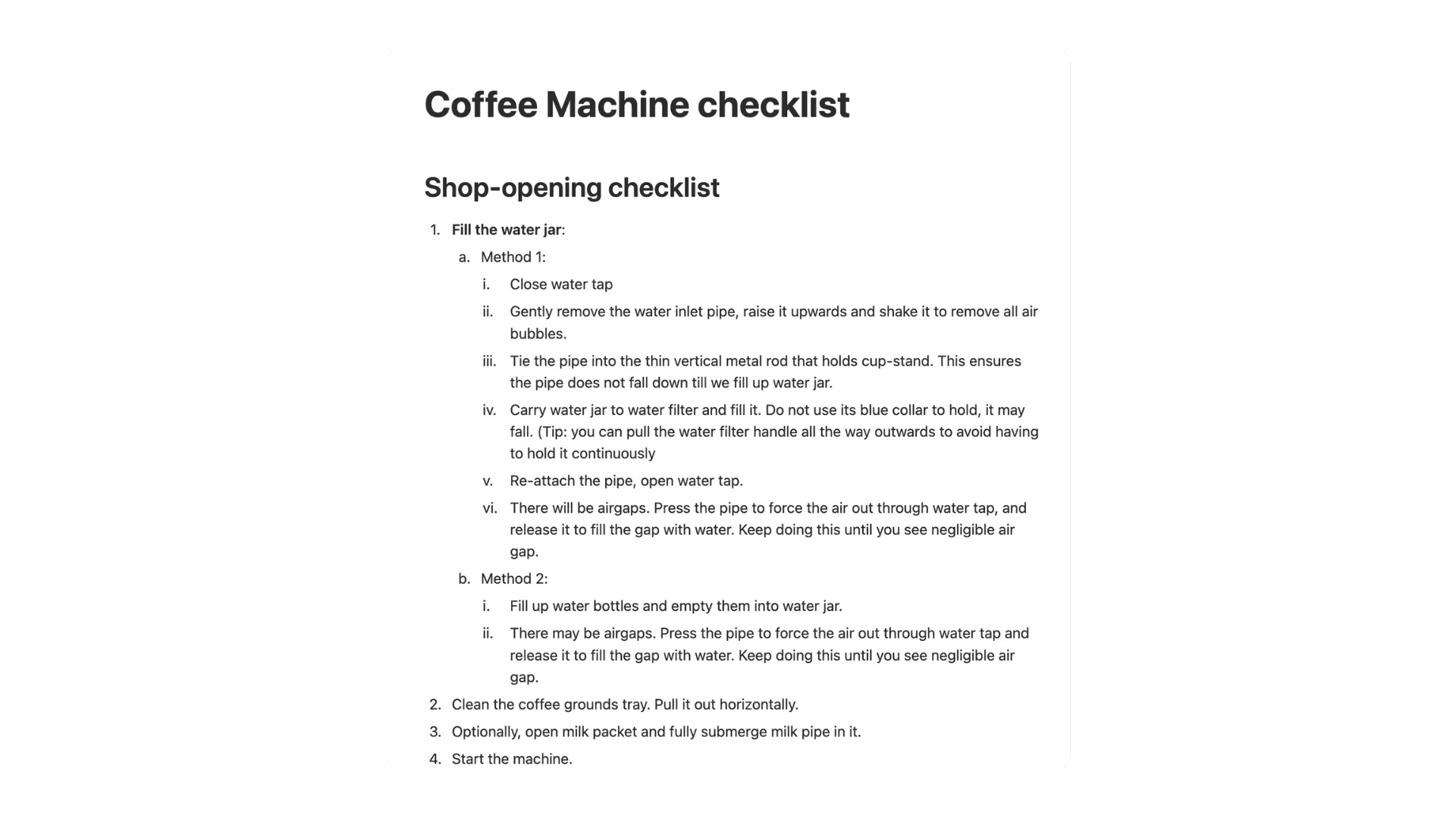

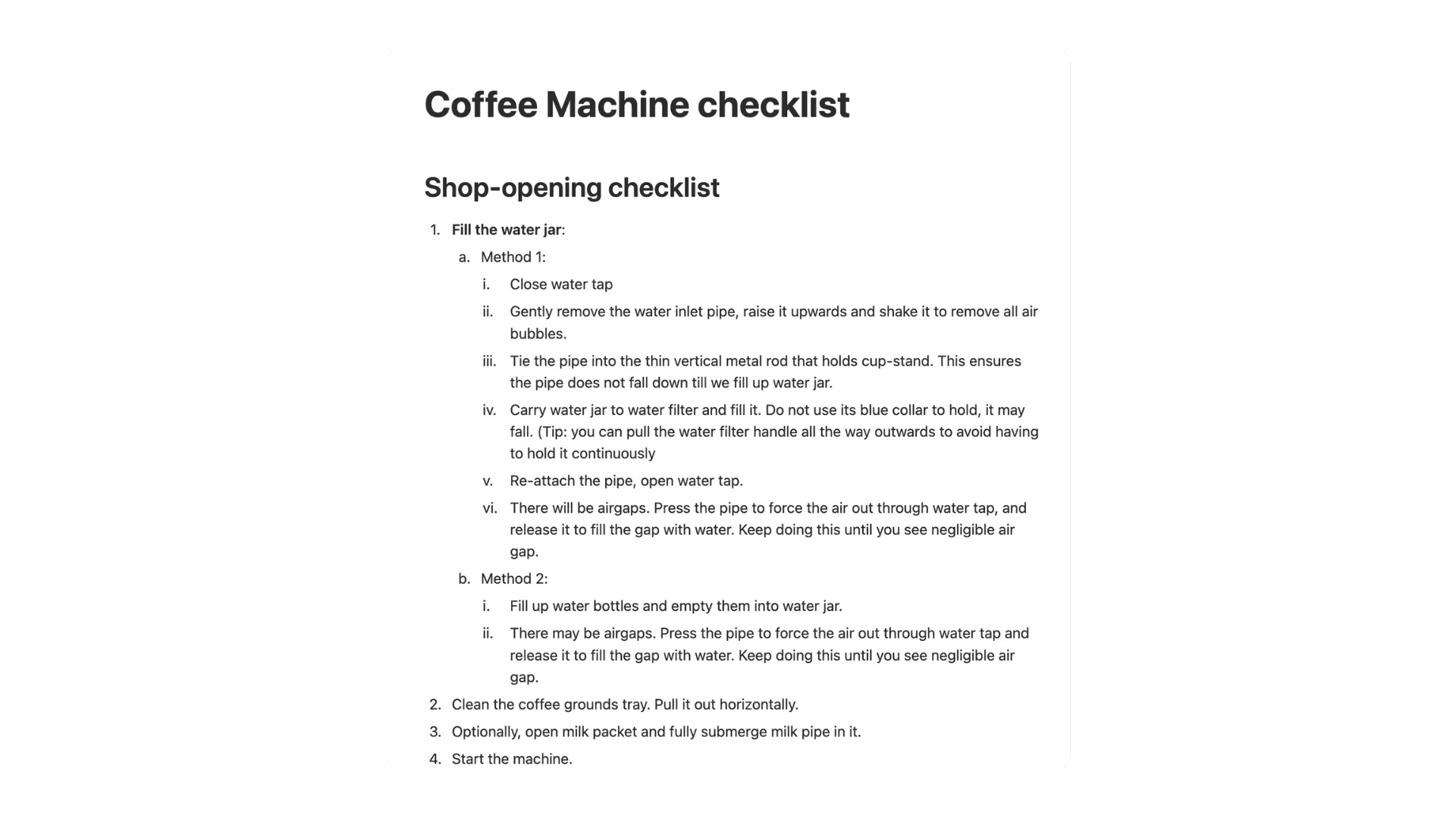

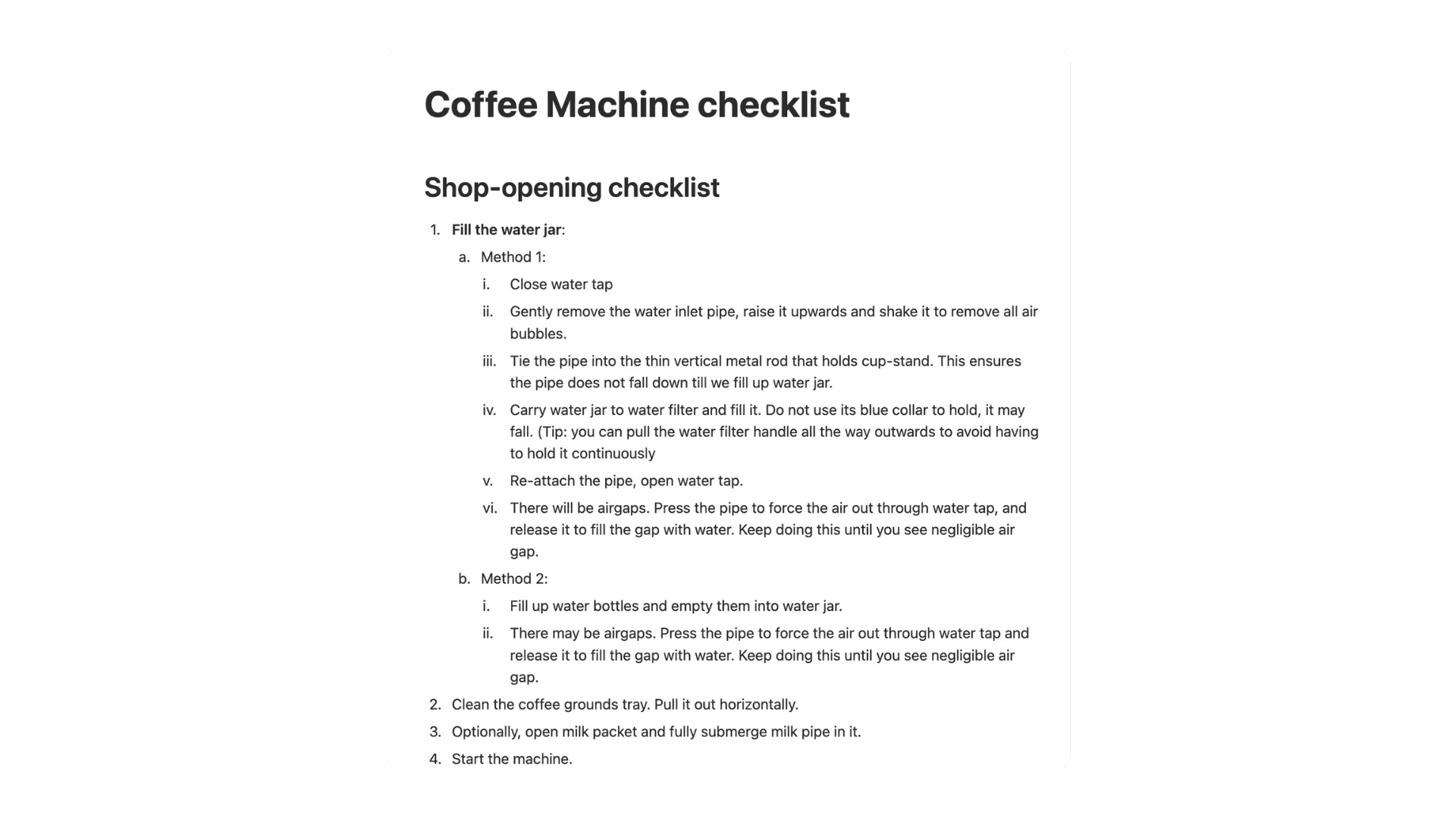

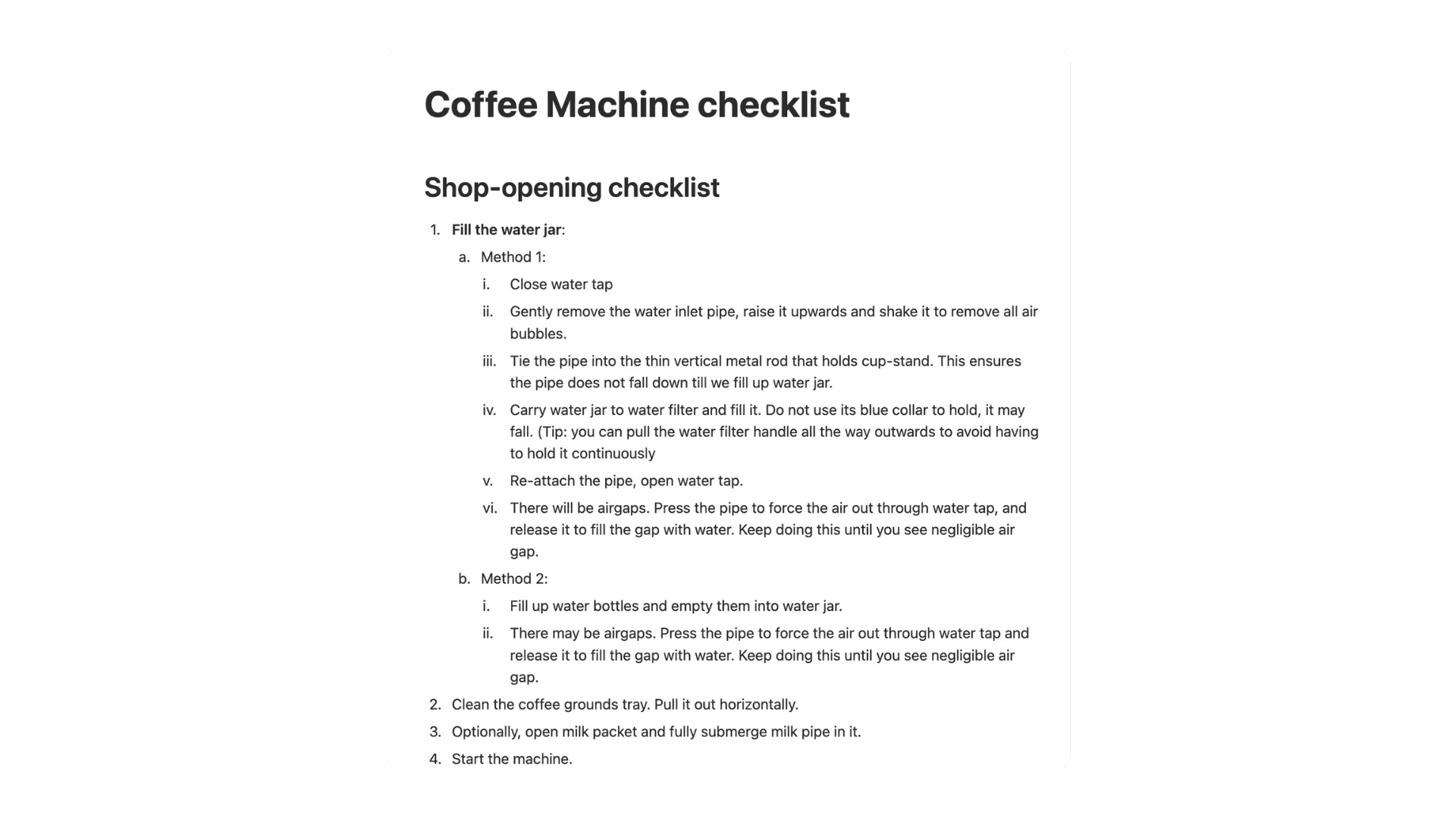

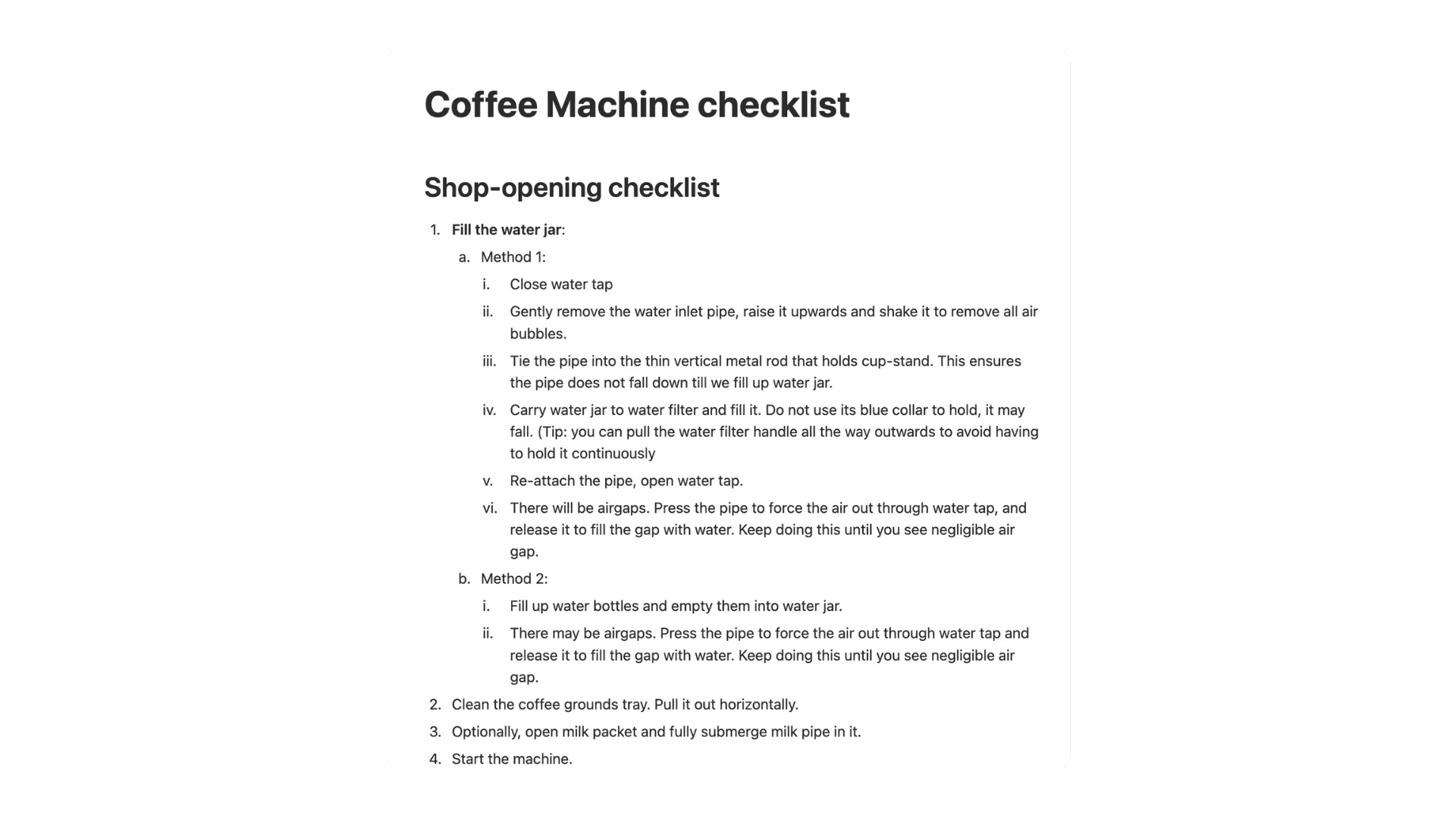

At the One2N office, we have a literal checklist for the coffee machine.

It is a simple 4-step process for cleaning and refilling. To an outsider, it might look like micromanagement. To us, it is a proxy for how we work. If we do not have the collective discipline to maintain a physical tool that the whole team relies on, how can we expect to maintain the integrity of a production system serving millions of users?

The 80/20 Rule of Engineering Hygiene

Engineering excellence is often sold as a series of “cool” technical choices. We talk about choosing the right database, the right framework, or the latest cloud-native tool. In practice, real-world reliability is 20% architectural design and 80% operational hygiene.

I have seen massive systems fail not because of a complex logic bug, but because of a “silent” mismatch in configuration that everyone assumed was correct. It is usually something unglamorous: a subtle drift in environment variables, a branching strategy that made rollbacks impossible during an outage, or an observability dashboard that looked green because the health checks were not exercising the real data path.

Peace of mind comes from reducing the surface area for these silent failures.

We focus on what I call Peace of Mind Engineering. The goal is to build systems where your team size does not need to scale linearly with traffic. You get that peace of mind from a culture that refuses to tolerate sloppiness in the small things.

A concrete example. One team we worked with had a well-architected stack on paper, but their deployment hygiene was weak. No standard rollback strategy, ad hoc dashboards, no clear ownership of alerts. Every incident needed half the team on a call. Once we fixed the “boring” parts (branching, runbooks, SLOs, observability, rollback patterns), the same traffic profile needed far fewer people to run. Nothing “cool” changed in the architecture, but the reliability and team capacity went up.

The coffee machine checklist is the same idea, just in physical form.

Practicing the Craft

You cannot just tell people to be disciplined. You have to give them a space to practice it.

This is why we created an internal laboratory we call Prayogshala.

When our engineers are not on a client engagement, they are in the lab. They are not just “playing” with tools. They are in a principal-led apprenticeship headed by Saurabh Hirani, our Principal SRE, whom we call CHOTU (Chief Head of Talent Upskilling).

Saurabh brings fifteen years of battle scars. When an engineer builds a Proof of Concept (POC) for something like OpenTelemetry or ClickHouse, he is not looking for a “Hello World” demo. He is looking for sharp edges.

Does the configuration management account for secret rotation without downtime?

Is the telemetry granular enough to catch a 1% failure rate that a generic 5xx alert would miss?

Does the solution solve for the business outcome, or is it just “cool tech”?

A recent internal POC on ClickHouse is a good example. The “happy path” ingestion worked in a day. The interesting part came later: handling schema evolution without breaking queries, validating backfill strategies for historical data, and designing retention policies that kept storage under control while preserving useful debug context. Those sharp edges surfaced long before any client workload touched the system.

This friction between an idea and a working, critiqued implementation is where real growth happens. We use this environment to make the “lities” muscle memory before our engineers ever touch a client’s production environment.

Culture happens when no one is watching

Most first-time leaders underestimate how costly it is to maintain a good culture. It is not a one-time effort. It is an every-time effort. We fall down to our habits rather than rise to our goals.

Through our lab, we build those habits.

We treat our internal Knowledge Base as a product. We update our Java Product Engineering Bootcamps and SRE Training modules based on what we learn in Prayogshala. We have standardized our CI/CD setups and backend architecture patterns so that we are not reinventing the wheel on every project.

We also use small, repeatable rituals to keep the bar high. For example:

Every new engineer ships an internal service to our staging environment end-to-end: code, CI/CD, observability, and runbook. Only after that do they get access to any client environment.

Every incident or sharp edge we discover in the lab must result in at least one change: a checklist item, a dashboard widget, a runbook step, or a training module update.

These are boring on purpose. Boring and repeatable beats clever and fragile when you are on call at 2 AM.

This culture of discipline allows us to work with portfolios from PeakXV, Accel, and Lightspeed with a level of confidence that is hard to find. These companies face modernization and cloud adoption issues that need more than diagramming boxes in an architecture review. They need practitioners who know which questions to ask before they write a single line of code.

The Influence of the Practitioner

Your influence as an engineer comes from your craft, not your title. Craft includes having the humility to follow a checklist. It includes caring about maintainability as much as you care about performance.

At One2N, we invest in internal rigor so that we are not just a company of people who “know” things, but a company of practitioners who “do” things. We build technology solutions that scale, but we do it by focusing on the small, unglamorous habits that make those systems possible.

Reliability is not a switch you turn on when you are writing code. It shows up in how you handle the coffee machine in the morning: whether you follow the checklist, refill it properly, clean it for the next person, and leave things a bit better than you found them.

If you are interested in how we operate, we have published it all in our playbook. If you are facing a hard engineering problem and need a team that focuses on craft over hype, let us talk.

I recently wrote about a concept that has stayed with me through every stage of my career: “Culture is not what you say, it is what you tolerate.”

It is easy to print values on a wall or run workshops on psychological safety. The hard part is that humans make mistakes. We are all prone to taking shortcuts when we are tired, under pressure, or overconfident. In high-stakes engineering, whether you are a funded startup or a $10B enterprise, those shortcuts are where the “lities” of a system begin to erode.

At the One2N office, we have a literal checklist for the coffee machine.

It is a simple 4-step process for cleaning and refilling. To an outsider, it might look like micromanagement. To us, it is a proxy for how we work. If we do not have the collective discipline to maintain a physical tool that the whole team relies on, how can we expect to maintain the integrity of a production system serving millions of users?

The 80/20 Rule of Engineering Hygiene

Engineering excellence is often sold as a series of “cool” technical choices. We talk about choosing the right database, the right framework, or the latest cloud-native tool. In practice, real-world reliability is 20% architectural design and 80% operational hygiene.

I have seen massive systems fail not because of a complex logic bug, but because of a “silent” mismatch in configuration that everyone assumed was correct. It is usually something unglamorous: a subtle drift in environment variables, a branching strategy that made rollbacks impossible during an outage, or an observability dashboard that looked green because the health checks were not exercising the real data path.

Peace of mind comes from reducing the surface area for these silent failures.

We focus on what I call Peace of Mind Engineering. The goal is to build systems where your team size does not need to scale linearly with traffic. You get that peace of mind from a culture that refuses to tolerate sloppiness in the small things.

A concrete example. One team we worked with had a well-architected stack on paper, but their deployment hygiene was weak. No standard rollback strategy, ad hoc dashboards, no clear ownership of alerts. Every incident needed half the team on a call. Once we fixed the “boring” parts (branching, runbooks, SLOs, observability, rollback patterns), the same traffic profile needed far fewer people to run. Nothing “cool” changed in the architecture, but the reliability and team capacity went up.

The coffee machine checklist is the same idea, just in physical form.

Practicing the Craft

You cannot just tell people to be disciplined. You have to give them a space to practice it.

This is why we created an internal laboratory we call Prayogshala.

When our engineers are not on a client engagement, they are in the lab. They are not just “playing” with tools. They are in a principal-led apprenticeship headed by Saurabh Hirani, our Principal SRE, whom we call CHOTU (Chief Head of Talent Upskilling).

Saurabh brings fifteen years of battle scars. When an engineer builds a Proof of Concept (POC) for something like OpenTelemetry or ClickHouse, he is not looking for a “Hello World” demo. He is looking for sharp edges.

Does the configuration management account for secret rotation without downtime?

Is the telemetry granular enough to catch a 1% failure rate that a generic 5xx alert would miss?

Does the solution solve for the business outcome, or is it just “cool tech”?

A recent internal POC on ClickHouse is a good example. The “happy path” ingestion worked in a day. The interesting part came later: handling schema evolution without breaking queries, validating backfill strategies for historical data, and designing retention policies that kept storage under control while preserving useful debug context. Those sharp edges surfaced long before any client workload touched the system.

This friction between an idea and a working, critiqued implementation is where real growth happens. We use this environment to make the “lities” muscle memory before our engineers ever touch a client’s production environment.

Culture happens when no one is watching

Most first-time leaders underestimate how costly it is to maintain a good culture. It is not a one-time effort. It is an every-time effort. We fall down to our habits rather than rise to our goals.

Through our lab, we build those habits.

We treat our internal Knowledge Base as a product. We update our Java Product Engineering Bootcamps and SRE Training modules based on what we learn in Prayogshala. We have standardized our CI/CD setups and backend architecture patterns so that we are not reinventing the wheel on every project.

We also use small, repeatable rituals to keep the bar high. For example:

Every new engineer ships an internal service to our staging environment end-to-end: code, CI/CD, observability, and runbook. Only after that do they get access to any client environment.

Every incident or sharp edge we discover in the lab must result in at least one change: a checklist item, a dashboard widget, a runbook step, or a training module update.

These are boring on purpose. Boring and repeatable beats clever and fragile when you are on call at 2 AM.

This culture of discipline allows us to work with portfolios from PeakXV, Accel, and Lightspeed with a level of confidence that is hard to find. These companies face modernization and cloud adoption issues that need more than diagramming boxes in an architecture review. They need practitioners who know which questions to ask before they write a single line of code.

The Influence of the Practitioner

Your influence as an engineer comes from your craft, not your title. Craft includes having the humility to follow a checklist. It includes caring about maintainability as much as you care about performance.

At One2N, we invest in internal rigor so that we are not just a company of people who “know” things, but a company of practitioners who “do” things. We build technology solutions that scale, but we do it by focusing on the small, unglamorous habits that make those systems possible.

Reliability is not a switch you turn on when you are writing code. It shows up in how you handle the coffee machine in the morning: whether you follow the checklist, refill it properly, clean it for the next person, and leave things a bit better than you found them.

If you are interested in how we operate, we have published it all in our playbook. If you are facing a hard engineering problem and need a team that focuses on craft over hype, let us talk.

I recently wrote about a concept that has stayed with me through every stage of my career: “Culture is not what you say, it is what you tolerate.”

It is easy to print values on a wall or run workshops on psychological safety. The hard part is that humans make mistakes. We are all prone to taking shortcuts when we are tired, under pressure, or overconfident. In high-stakes engineering, whether you are a funded startup or a $10B enterprise, those shortcuts are where the “lities” of a system begin to erode.

At the One2N office, we have a literal checklist for the coffee machine.

It is a simple 4-step process for cleaning and refilling. To an outsider, it might look like micromanagement. To us, it is a proxy for how we work. If we do not have the collective discipline to maintain a physical tool that the whole team relies on, how can we expect to maintain the integrity of a production system serving millions of users?

The 80/20 Rule of Engineering Hygiene

Engineering excellence is often sold as a series of “cool” technical choices. We talk about choosing the right database, the right framework, or the latest cloud-native tool. In practice, real-world reliability is 20% architectural design and 80% operational hygiene.

I have seen massive systems fail not because of a complex logic bug, but because of a “silent” mismatch in configuration that everyone assumed was correct. It is usually something unglamorous: a subtle drift in environment variables, a branching strategy that made rollbacks impossible during an outage, or an observability dashboard that looked green because the health checks were not exercising the real data path.

Peace of mind comes from reducing the surface area for these silent failures.

We focus on what I call Peace of Mind Engineering. The goal is to build systems where your team size does not need to scale linearly with traffic. You get that peace of mind from a culture that refuses to tolerate sloppiness in the small things.

A concrete example. One team we worked with had a well-architected stack on paper, but their deployment hygiene was weak. No standard rollback strategy, ad hoc dashboards, no clear ownership of alerts. Every incident needed half the team on a call. Once we fixed the “boring” parts (branching, runbooks, SLOs, observability, rollback patterns), the same traffic profile needed far fewer people to run. Nothing “cool” changed in the architecture, but the reliability and team capacity went up.

The coffee machine checklist is the same idea, just in physical form.

Practicing the Craft

You cannot just tell people to be disciplined. You have to give them a space to practice it.

This is why we created an internal laboratory we call Prayogshala.

When our engineers are not on a client engagement, they are in the lab. They are not just “playing” with tools. They are in a principal-led apprenticeship headed by Saurabh Hirani, our Principal SRE, whom we call CHOTU (Chief Head of Talent Upskilling).

Saurabh brings fifteen years of battle scars. When an engineer builds a Proof of Concept (POC) for something like OpenTelemetry or ClickHouse, he is not looking for a “Hello World” demo. He is looking for sharp edges.

Does the configuration management account for secret rotation without downtime?

Is the telemetry granular enough to catch a 1% failure rate that a generic 5xx alert would miss?

Does the solution solve for the business outcome, or is it just “cool tech”?

A recent internal POC on ClickHouse is a good example. The “happy path” ingestion worked in a day. The interesting part came later: handling schema evolution without breaking queries, validating backfill strategies for historical data, and designing retention policies that kept storage under control while preserving useful debug context. Those sharp edges surfaced long before any client workload touched the system.

This friction between an idea and a working, critiqued implementation is where real growth happens. We use this environment to make the “lities” muscle memory before our engineers ever touch a client’s production environment.

Culture happens when no one is watching

Most first-time leaders underestimate how costly it is to maintain a good culture. It is not a one-time effort. It is an every-time effort. We fall down to our habits rather than rise to our goals.

Through our lab, we build those habits.

We treat our internal Knowledge Base as a product. We update our Java Product Engineering Bootcamps and SRE Training modules based on what we learn in Prayogshala. We have standardized our CI/CD setups and backend architecture patterns so that we are not reinventing the wheel on every project.

We also use small, repeatable rituals to keep the bar high. For example:

Every new engineer ships an internal service to our staging environment end-to-end: code, CI/CD, observability, and runbook. Only after that do they get access to any client environment.

Every incident or sharp edge we discover in the lab must result in at least one change: a checklist item, a dashboard widget, a runbook step, or a training module update.

These are boring on purpose. Boring and repeatable beats clever and fragile when you are on call at 2 AM.

This culture of discipline allows us to work with portfolios from PeakXV, Accel, and Lightspeed with a level of confidence that is hard to find. These companies face modernization and cloud adoption issues that need more than diagramming boxes in an architecture review. They need practitioners who know which questions to ask before they write a single line of code.

The Influence of the Practitioner

Your influence as an engineer comes from your craft, not your title. Craft includes having the humility to follow a checklist. It includes caring about maintainability as much as you care about performance.

At One2N, we invest in internal rigor so that we are not just a company of people who “know” things, but a company of practitioners who “do” things. We build technology solutions that scale, but we do it by focusing on the small, unglamorous habits that make those systems possible.

Reliability is not a switch you turn on when you are writing code. It shows up in how you handle the coffee machine in the morning: whether you follow the checklist, refill it properly, clean it for the next person, and leave things a bit better than you found them.

If you are interested in how we operate, we have published it all in our playbook. If you are facing a hard engineering problem and need a team that focuses on craft over hype, let us talk.

I recently wrote about a concept that has stayed with me through every stage of my career: “Culture is not what you say, it is what you tolerate.”

It is easy to print values on a wall or run workshops on psychological safety. The hard part is that humans make mistakes. We are all prone to taking shortcuts when we are tired, under pressure, or overconfident. In high-stakes engineering, whether you are a funded startup or a $10B enterprise, those shortcuts are where the “lities” of a system begin to erode.

At the One2N office, we have a literal checklist for the coffee machine.

It is a simple 4-step process for cleaning and refilling. To an outsider, it might look like micromanagement. To us, it is a proxy for how we work. If we do not have the collective discipline to maintain a physical tool that the whole team relies on, how can we expect to maintain the integrity of a production system serving millions of users?

The 80/20 Rule of Engineering Hygiene

Engineering excellence is often sold as a series of “cool” technical choices. We talk about choosing the right database, the right framework, or the latest cloud-native tool. In practice, real-world reliability is 20% architectural design and 80% operational hygiene.

I have seen massive systems fail not because of a complex logic bug, but because of a “silent” mismatch in configuration that everyone assumed was correct. It is usually something unglamorous: a subtle drift in environment variables, a branching strategy that made rollbacks impossible during an outage, or an observability dashboard that looked green because the health checks were not exercising the real data path.

Peace of mind comes from reducing the surface area for these silent failures.

We focus on what I call Peace of Mind Engineering. The goal is to build systems where your team size does not need to scale linearly with traffic. You get that peace of mind from a culture that refuses to tolerate sloppiness in the small things.

A concrete example. One team we worked with had a well-architected stack on paper, but their deployment hygiene was weak. No standard rollback strategy, ad hoc dashboards, no clear ownership of alerts. Every incident needed half the team on a call. Once we fixed the “boring” parts (branching, runbooks, SLOs, observability, rollback patterns), the same traffic profile needed far fewer people to run. Nothing “cool” changed in the architecture, but the reliability and team capacity went up.

The coffee machine checklist is the same idea, just in physical form.

Practicing the Craft

You cannot just tell people to be disciplined. You have to give them a space to practice it.

This is why we created an internal laboratory we call Prayogshala.

When our engineers are not on a client engagement, they are in the lab. They are not just “playing” with tools. They are in a principal-led apprenticeship headed by Saurabh Hirani, our Principal SRE, whom we call CHOTU (Chief Head of Talent Upskilling).

Saurabh brings fifteen years of battle scars. When an engineer builds a Proof of Concept (POC) for something like OpenTelemetry or ClickHouse, he is not looking for a “Hello World” demo. He is looking for sharp edges.

Does the configuration management account for secret rotation without downtime?

Is the telemetry granular enough to catch a 1% failure rate that a generic 5xx alert would miss?

Does the solution solve for the business outcome, or is it just “cool tech”?

A recent internal POC on ClickHouse is a good example. The “happy path” ingestion worked in a day. The interesting part came later: handling schema evolution without breaking queries, validating backfill strategies for historical data, and designing retention policies that kept storage under control while preserving useful debug context. Those sharp edges surfaced long before any client workload touched the system.

This friction between an idea and a working, critiqued implementation is where real growth happens. We use this environment to make the “lities” muscle memory before our engineers ever touch a client’s production environment.

Culture happens when no one is watching

Most first-time leaders underestimate how costly it is to maintain a good culture. It is not a one-time effort. It is an every-time effort. We fall down to our habits rather than rise to our goals.

Through our lab, we build those habits.

We treat our internal Knowledge Base as a product. We update our Java Product Engineering Bootcamps and SRE Training modules based on what we learn in Prayogshala. We have standardized our CI/CD setups and backend architecture patterns so that we are not reinventing the wheel on every project.

We also use small, repeatable rituals to keep the bar high. For example:

Every new engineer ships an internal service to our staging environment end-to-end: code, CI/CD, observability, and runbook. Only after that do they get access to any client environment.

Every incident or sharp edge we discover in the lab must result in at least one change: a checklist item, a dashboard widget, a runbook step, or a training module update.

These are boring on purpose. Boring and repeatable beats clever and fragile when you are on call at 2 AM.

This culture of discipline allows us to work with portfolios from PeakXV, Accel, and Lightspeed with a level of confidence that is hard to find. These companies face modernization and cloud adoption issues that need more than diagramming boxes in an architecture review. They need practitioners who know which questions to ask before they write a single line of code.

The Influence of the Practitioner

Your influence as an engineer comes from your craft, not your title. Craft includes having the humility to follow a checklist. It includes caring about maintainability as much as you care about performance.

At One2N, we invest in internal rigor so that we are not just a company of people who “know” things, but a company of practitioners who “do” things. We build technology solutions that scale, but we do it by focusing on the small, unglamorous habits that make those systems possible.

Reliability is not a switch you turn on when you are writing code. It shows up in how you handle the coffee machine in the morning: whether you follow the checklist, refill it properly, clean it for the next person, and leave things a bit better than you found them.

If you are interested in how we operate, we have published it all in our playbook. If you are facing a hard engineering problem and need a team that focuses on craft over hype, let us talk.

I recently wrote about a concept that has stayed with me through every stage of my career: “Culture is not what you say, it is what you tolerate.”

It is easy to print values on a wall or run workshops on psychological safety. The hard part is that humans make mistakes. We are all prone to taking shortcuts when we are tired, under pressure, or overconfident. In high-stakes engineering, whether you are a funded startup or a $10B enterprise, those shortcuts are where the “lities” of a system begin to erode.

At the One2N office, we have a literal checklist for the coffee machine.

It is a simple 4-step process for cleaning and refilling. To an outsider, it might look like micromanagement. To us, it is a proxy for how we work. If we do not have the collective discipline to maintain a physical tool that the whole team relies on, how can we expect to maintain the integrity of a production system serving millions of users?

The 80/20 Rule of Engineering Hygiene

Engineering excellence is often sold as a series of “cool” technical choices. We talk about choosing the right database, the right framework, or the latest cloud-native tool. In practice, real-world reliability is 20% architectural design and 80% operational hygiene.

I have seen massive systems fail not because of a complex logic bug, but because of a “silent” mismatch in configuration that everyone assumed was correct. It is usually something unglamorous: a subtle drift in environment variables, a branching strategy that made rollbacks impossible during an outage, or an observability dashboard that looked green because the health checks were not exercising the real data path.

Peace of mind comes from reducing the surface area for these silent failures.

We focus on what I call Peace of Mind Engineering. The goal is to build systems where your team size does not need to scale linearly with traffic. You get that peace of mind from a culture that refuses to tolerate sloppiness in the small things.

A concrete example. One team we worked with had a well-architected stack on paper, but their deployment hygiene was weak. No standard rollback strategy, ad hoc dashboards, no clear ownership of alerts. Every incident needed half the team on a call. Once we fixed the “boring” parts (branching, runbooks, SLOs, observability, rollback patterns), the same traffic profile needed far fewer people to run. Nothing “cool” changed in the architecture, but the reliability and team capacity went up.

The coffee machine checklist is the same idea, just in physical form.

Practicing the Craft

You cannot just tell people to be disciplined. You have to give them a space to practice it.

This is why we created an internal laboratory we call Prayogshala.

When our engineers are not on a client engagement, they are in the lab. They are not just “playing” with tools. They are in a principal-led apprenticeship headed by Saurabh Hirani, our Principal SRE, whom we call CHOTU (Chief Head of Talent Upskilling).

Saurabh brings fifteen years of battle scars. When an engineer builds a Proof of Concept (POC) for something like OpenTelemetry or ClickHouse, he is not looking for a “Hello World” demo. He is looking for sharp edges.

Does the configuration management account for secret rotation without downtime?

Is the telemetry granular enough to catch a 1% failure rate that a generic 5xx alert would miss?

Does the solution solve for the business outcome, or is it just “cool tech”?

A recent internal POC on ClickHouse is a good example. The “happy path” ingestion worked in a day. The interesting part came later: handling schema evolution without breaking queries, validating backfill strategies for historical data, and designing retention policies that kept storage under control while preserving useful debug context. Those sharp edges surfaced long before any client workload touched the system.

This friction between an idea and a working, critiqued implementation is where real growth happens. We use this environment to make the “lities” muscle memory before our engineers ever touch a client’s production environment.

Culture happens when no one is watching

Most first-time leaders underestimate how costly it is to maintain a good culture. It is not a one-time effort. It is an every-time effort. We fall down to our habits rather than rise to our goals.

Through our lab, we build those habits.

We treat our internal Knowledge Base as a product. We update our Java Product Engineering Bootcamps and SRE Training modules based on what we learn in Prayogshala. We have standardized our CI/CD setups and backend architecture patterns so that we are not reinventing the wheel on every project.

We also use small, repeatable rituals to keep the bar high. For example:

Every new engineer ships an internal service to our staging environment end-to-end: code, CI/CD, observability, and runbook. Only after that do they get access to any client environment.

Every incident or sharp edge we discover in the lab must result in at least one change: a checklist item, a dashboard widget, a runbook step, or a training module update.

These are boring on purpose. Boring and repeatable beats clever and fragile when you are on call at 2 AM.

This culture of discipline allows us to work with portfolios from PeakXV, Accel, and Lightspeed with a level of confidence that is hard to find. These companies face modernization and cloud adoption issues that need more than diagramming boxes in an architecture review. They need practitioners who know which questions to ask before they write a single line of code.

The Influence of the Practitioner

Your influence as an engineer comes from your craft, not your title. Craft includes having the humility to follow a checklist. It includes caring about maintainability as much as you care about performance.

At One2N, we invest in internal rigor so that we are not just a company of people who “know” things, but a company of practitioners who “do” things. We build technology solutions that scale, but we do it by focusing on the small, unglamorous habits that make those systems possible.

Reliability is not a switch you turn on when you are writing code. It shows up in how you handle the coffee machine in the morning: whether you follow the checklist, refill it properly, clean it for the next person, and leave things a bit better than you found them.

If you are interested in how we operate, we have published it all in our playbook. If you are facing a hard engineering problem and need a team that focuses on craft over hype, let us talk.